Suzanne Stein: US: Slow Code : Verena Kerfin Gallery, Köthener Strasse 28, Berlin 10963

Current

exhibition

Overview

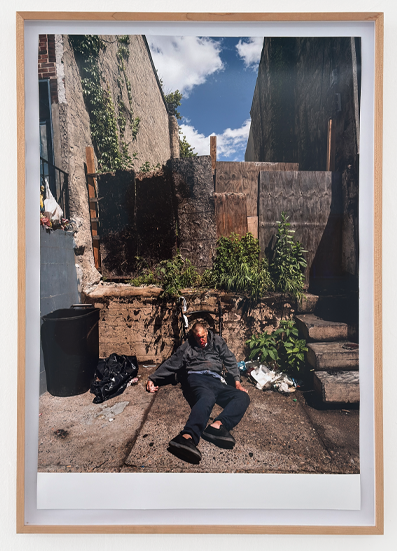

Suzanne Stein is an American street photographer. She does not work on images that soothe. She works on images that unsettle.

Tranq: no myth, no metaphor. Necrosis as a byproduct of a supply chain. Stein shows a system in which the substance causes the wound and remains, at the same time, the condition under which a person can still function at all. Healing is no longer a medical process; it becomes a question of access, time, transport, admission. If you don’t fit, you stay outside. If you stay outside, you remain open on the body.

A new class of disability forms in a country that tells itself it is capable. Young bodies in wheelchairs because legs no longer hold; arms, hands, feet missing or unusable. Half-alive, like a battlefield, reporting the victory of the other side—the side that has more. This is not a footnote to the opioid crisis; it is its infrastructure. Wounds stay open because daily life has no time for dressings, because pain management is chained to the drug, because hospitals are experienced as hostile terrain, because withdrawal is felt as more immediate than the loss of a limb. The body becomes the site of settlement: shipment against tissue, high against blood, dose against circulation.

Kensington is not “misery.” Kensington is the form misery takes when it is organized inside a wealthy state: visible enough to serve as deterrent, invisible enough to remain politically consequence-free. America as poorhouse—not because money is absent, but because it is arranged so that people live and die this way while the rest maintains the routine.

Housing is the second necessary supply. If you have no room, you become the room: a surface for stares, police routines, outreach shifts, dealer time. Stein does not tie the street scene to Christian stories of good and evil or hope; she ties it to an economy of rent, displacement, scarce rooms, permanent cancellability. This is the quiet violence that turns a life into a provisional state—until the provisional becomes the only state known. The lease as blade. The eviction notice as calendar. The address as border.

Old age is also given economic form. An elderly woman, decades in the same place, now frail, ill, alone, dependent on a few friends—not unhoused, but marked by the same disappearance: social safety nets withdrawing; relationships thinning; a healthcare system that does not catch the weak, but administers them. Poverty in old age does not necessarily mean the street. It means enclosed time. Stairs that become too steep. Pain that shrinks the radius. An inner overload that manifests outwardly. Pets whose loss tips the remaining stability. The apartment remains, but life contracts inside it. Inside grows tight. Outside grows far.

Poor and rich in the United States is no longer a contrast; it is coexistence without contact. Six feet apart, two worlds. One space is air-conditioned, the other is asphalt. One space treats safety as a given; the other knows safety only as exception. And above both stand gatekeepers: editors, platforms, institutions that decide what is shown and what is “too much.” Stein names this prudishness as part of the problem. If you don’t see it, there is no responsibility; whoever controls visibility controls responsibility. The invisible becomes tolerable. The visible is assigned blame.

Street photography no longer sits in the field of styles; it sits in the field of duty. But duty is not a medal. Duty is work at a boundary. In Kensington, trust is not a nice add-on; it is the only way not to become a target of violence immediately. At the same time, that trust remains brittle. Stein describes how she herself became a target, how images of her circulated, how freedom of movement becomes a negotiated quantity. Street photography as a practice under pressure: gaze and countergaze, camera and consequence. A body with a camera is not neutral. It is a factor—possibly an attack, or also a target.

Visibility does not only attract attention; it attracts exploitation. Whoever documents leaves a trace, and others can use that trace to harass, hunt, use people. Good intention does not protect against harm. Documentation can injure, even when it is necessary; looking away can be worse, even when it feels “clean.” The task sits inside this tension: drawing the boundary again and again, without buying oneself off with one’s own “stance.”

Beauty can be a filter that removes the demand. Stein refuses that sedation. Her work is not shock porn, precisely because she does not take her subjects as trophies. She insists on the necessity of hardness—not to triumph, but to sabotage the normalization of damage. When she says anger is her engine, that anger is not a stylistic device; it is counter-energy against the routinized passing-by. Against the ease of the monstrous.

Tranq, elder poverty, homelessness: not separate chapters, a continuum of precarity. A body tips when care tips. A life tips when housing tips. A neighborhood tips when politics tips—or, more precisely, when politics specializes in managing the tipping instead of preventing it. In the United States, this management is often private, fragmented, profitable. Illness becomes a cost question. Dignity a time question. Safety a ZIP-code question. Stein does not show “the poor.” She shows the machine that produces poverty and then pretends it is natural.

Street photography has a clear, uncomfortable function here: memory against forgetting in the same moment. Evidence against the excuse that one “didn’t know.” Self-examination, because the camera has to be asked whether it helps or steals.

When people talk about America today, they too often talk in stories: dream, freedom, ascent. Stein’s work forces a different grammar: wound, rent, withdrawal, stairs, wheelchair, heat, flies, clinic, shame. Words that do not fit slogans. Words that do not console. Words that count the lack.

Tranq: no myth, no metaphor. Necrosis as a byproduct of a supply chain. Stein shows a system in which the substance causes the wound and remains, at the same time, the condition under which a person can still function at all. Healing is no longer a medical process; it becomes a question of access, time, transport, admission. If you don’t fit, you stay outside. If you stay outside, you remain open on the body.

A new class of disability forms in a country that tells itself it is capable. Young bodies in wheelchairs because legs no longer hold; arms, hands, feet missing or unusable. Half-alive, like a battlefield, reporting the victory of the other side—the side that has more. This is not a footnote to the opioid crisis; it is its infrastructure. Wounds stay open because daily life has no time for dressings, because pain management is chained to the drug, because hospitals are experienced as hostile terrain, because withdrawal is felt as more immediate than the loss of a limb. The body becomes the site of settlement: shipment against tissue, high against blood, dose against circulation.

Kensington is not “misery.” Kensington is the form misery takes when it is organized inside a wealthy state: visible enough to serve as deterrent, invisible enough to remain politically consequence-free. America as poorhouse—not because money is absent, but because it is arranged so that people live and die this way while the rest maintains the routine.

Housing is the second necessary supply. If you have no room, you become the room: a surface for stares, police routines, outreach shifts, dealer time. Stein does not tie the street scene to Christian stories of good and evil or hope; she ties it to an economy of rent, displacement, scarce rooms, permanent cancellability. This is the quiet violence that turns a life into a provisional state—until the provisional becomes the only state known. The lease as blade. The eviction notice as calendar. The address as border.

Old age is also given economic form. An elderly woman, decades in the same place, now frail, ill, alone, dependent on a few friends—not unhoused, but marked by the same disappearance: social safety nets withdrawing; relationships thinning; a healthcare system that does not catch the weak, but administers them. Poverty in old age does not necessarily mean the street. It means enclosed time. Stairs that become too steep. Pain that shrinks the radius. An inner overload that manifests outwardly. Pets whose loss tips the remaining stability. The apartment remains, but life contracts inside it. Inside grows tight. Outside grows far.

Poor and rich in the United States is no longer a contrast; it is coexistence without contact. Six feet apart, two worlds. One space is air-conditioned, the other is asphalt. One space treats safety as a given; the other knows safety only as exception. And above both stand gatekeepers: editors, platforms, institutions that decide what is shown and what is “too much.” Stein names this prudishness as part of the problem. If you don’t see it, there is no responsibility; whoever controls visibility controls responsibility. The invisible becomes tolerable. The visible is assigned blame.

Street photography no longer sits in the field of styles; it sits in the field of duty. But duty is not a medal. Duty is work at a boundary. In Kensington, trust is not a nice add-on; it is the only way not to become a target of violence immediately. At the same time, that trust remains brittle. Stein describes how she herself became a target, how images of her circulated, how freedom of movement becomes a negotiated quantity. Street photography as a practice under pressure: gaze and countergaze, camera and consequence. A body with a camera is not neutral. It is a factor—possibly an attack, or also a target.

Visibility does not only attract attention; it attracts exploitation. Whoever documents leaves a trace, and others can use that trace to harass, hunt, use people. Good intention does not protect against harm. Documentation can injure, even when it is necessary; looking away can be worse, even when it feels “clean.” The task sits inside this tension: drawing the boundary again and again, without buying oneself off with one’s own “stance.”

Beauty can be a filter that removes the demand. Stein refuses that sedation. Her work is not shock porn, precisely because she does not take her subjects as trophies. She insists on the necessity of hardness—not to triumph, but to sabotage the normalization of damage. When she says anger is her engine, that anger is not a stylistic device; it is counter-energy against the routinized passing-by. Against the ease of the monstrous.

Tranq, elder poverty, homelessness: not separate chapters, a continuum of precarity. A body tips when care tips. A life tips when housing tips. A neighborhood tips when politics tips—or, more precisely, when politics specializes in managing the tipping instead of preventing it. In the United States, this management is often private, fragmented, profitable. Illness becomes a cost question. Dignity a time question. Safety a ZIP-code question. Stein does not show “the poor.” She shows the machine that produces poverty and then pretends it is natural.

Street photography has a clear, uncomfortable function here: memory against forgetting in the same moment. Evidence against the excuse that one “didn’t know.” Self-examination, because the camera has to be asked whether it helps or steals.

When people talk about America today, they too often talk in stories: dream, freedom, ascent. Stein’s work forces a different grammar: wound, rent, withdrawal, stairs, wheelchair, heat, flies, clinic, shame. Words that do not fit slogans. Words that do not console. Words that count the lack.

Installation Views

×

![]()

Works

-

Suzanne SteinBethany Sleeps at 6th Avenue and 8th Street, 2019

Suzanne SteinBethany Sleeps at 6th Avenue and 8th Street, 2019 -

Suzanne SteinBillions, 2020

Suzanne SteinBillions, 2020 -

Suzanne SteinGeorge, 2022

Suzanne SteinGeorge, 2022 -

Suzanne SteinGinette, 2019

Suzanne SteinGinette, 2019 -

Suzanne SteinHazel on Pacific Street, 2024

Suzanne SteinHazel on Pacific Street, 2024 -

Suzanne SteinKensington and Lehigh Avenues, 2023

Suzanne SteinKensington and Lehigh Avenues, 2023 -

Suzanne SteinLeight, Stephanie, Nathalie and Ava, 2025

Suzanne SteinLeight, Stephanie, Nathalie and Ava, 2025 -

Suzanne SteinMike and Krystal, 2022

Suzanne SteinMike and Krystal, 2022 -

Suzanne SteinNoah, 2021

Suzanne SteinNoah, 2021 -

Suzanne SteinRico and Gene on Ruth Street, 2023

Suzanne SteinRico and Gene on Ruth Street, 2023 -

Suzanne SteinTranq Wound, 2022

Suzanne SteinTranq Wound, 2022 -

Suzanne Steinuntitled, 2023

Suzanne Steinuntitled, 2023 -

Suzanne SteinWest Gurney Street, 2022

Suzanne SteinWest Gurney Street, 2022

×