Lucas Pertile: Monkey Island : Verena Kerfin Gallery, Köthener Strasse 28, Berlin 10963

Past

exhibition

Overview

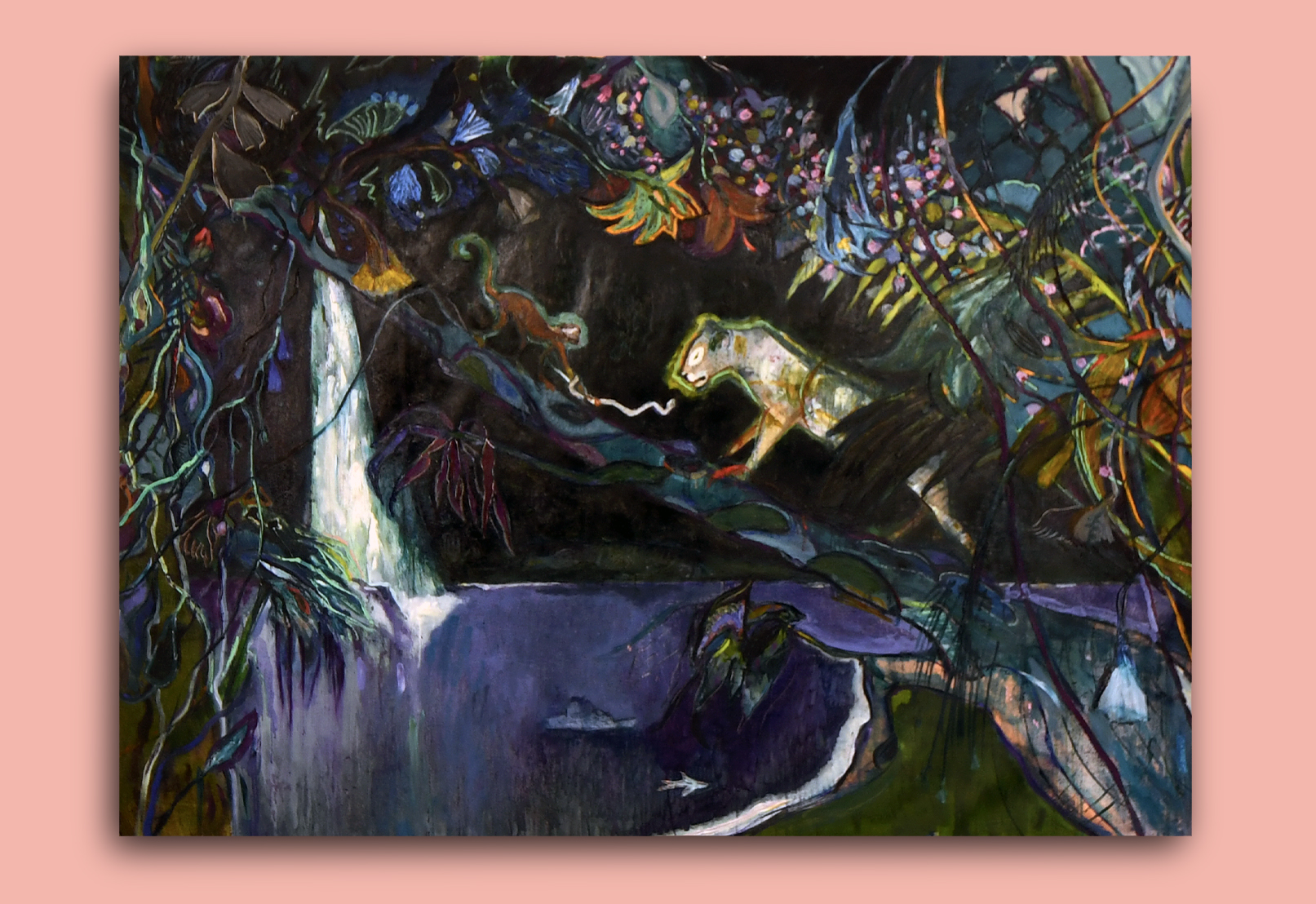

The country of Argentina, where Lucas Pertile lives, has two faces. In the south, the country stretches pointedly towards Antarctica, Tierra del Fuego and the South Shetland Islands are only a tiny bit apart, and between them rage the icy storms of the Cape Horn Passage. Patagonia forms the icy interlock into the sky so that this part is not blown away. In the north, Argentina is tropical. Between the countries of Uruguay and Paraguay, an argentinean headland also stretches out deep into the tropical rainforest of Brazil. There, one of the largest waterfalls on earth, the Iguazú Falls, spreads out over 2,7 km. Its noise is deafening. An intense roar that lies somewhere between a rumble and a howl, and to this the flora adds the chirping of crickets, the screaming of howler monkeys and the chorus of birds with endless voices. This rainforest in north–eastern Argentina is home to thousands of plant species, hundreds of bird species, exotic mammals such as lowland tapir, white–bearded peccary, capybara, brown howler monkey, hooded capuchin, southern tamandua, great anteater, ocelot, southern tiger cat, jaguarundi, forest dog, coati, crab raccoon, giant otter, South American otter and also many endangered animals like the jaguar. In the humid heat of the rainforest, a soundscape of wildlife arises at night that can be frightening. What a wonderfully diffuse place, which in its indeterminate appearances, describes precisely the place where the myths and spirits of Latin America fraternise with the everyday life of realism and allow creatures and apparitions from the myths to enter the present. The tales focus on dangers and on the Evil Spirit of Luz Mala, to this the Pombero Spirit warns whistling in the night.

Lucas Pertile grew up on the banks of a dark river, the Rio Negro. The Rio Negro is one of the largest tributaries in the world with an enormous mass of water, it flows as a tributary into the Amazon in northern Brazil. It carries black water from a marshy bottom with a nauseating smell, it is inhabited by tough fish with sharp scales that groan when you catch them. Fish that look like they come from prehistoric times. As a child, Lucas had to use a machete to make his way through the dense undergrowth on its banks. Since the age of five, he swam in the murky water that flowed past his house. At the same age, he crossed the river on a tree trunk that his brother had cut down shortly before. He ate water hyacinths. He raised a monkey. At ten, he went fishing with his friends and slept under the stars or in improvised shelters made of bark and branches that protected him from the tropical night.

His grandfather was a painter and his studio had been a familiar place for Lucas since childhood. The grandfather’s studio was a magical place to which not everyone had access, but which had such a strong attraction for Lucas that he never wanted to leave it as a child. His grandfather gave him pencils and let him copy his own pictures. He was a gruff man who found his calling as an artist early on. The art school in Resistencia, Chaco, bears his name: Alfredo Pertile. His grandmother grew flowers, and anyone who knows the life story of the writer Horacio Quiroga, who also had a refuge in Misiones at the beginning of the 20th century, knows that besides countless ants, there is an inordinate force of rainforest capture that makes every flower cultivation a self–sacrificing odyssey. Therefore it is obvious that the spirit of the Pertile family is linked to the flaring of flowers and wild tendrils of plants, and so it is logical that the hut in Misiones in the middle of the rainforest is the source of inspiration for his painting.

The evening light shines over the treetops of the rainforest like burning sparks. Whoever watches the videos on Lucas’ Instagram account shudders at the beauty of this strange natural spectacle. It is accompanied by an ever–present buzzing, as if the insect world were the actual body of nature, invisible but wide awake. The immediate impression is that the rainforest is living under high tension, living for itself, looking inwards with all its creatures on their own, hunt, rest, screaming and seeking other creatures. They act in a hidden way. The individual human being is drawn into this web of life as if into quicksand. Urban realities, human action and communication are only one variation among hundreds of thousands in this mesh. But even here cracks are appearing. Human intrusion into almost all habitats of the world is also taking its toll here. The beautiful jaguar is not the only creature whose species is pushed to the brink of extinction. Through the opening in the foliage, through strands of lianas, one can see out of the inner, intimate capsule of the rainforest in Lucas’ paintings to river mouths, sea accesses, to navigable passages. These are the gateways of human civilisation, eyed suspiciously through the tangle of vegetation, vicariously by the apes in his paintings. But the animal creatures are still playing their own mythical game in the body of the rainforest, occasionally swallowing Lucas inside as their equal.

Lucas’ paintings tell of the wilderness, they describe the living wilderness, with agitated, sometimes strongly gestural traces of painting. Everything seems to be in motion, the leaves seem dynamic like horses, the horses wild like a storm and the monkeys seem to be secretly trying out their own society among themselves, making their own coalitions, telling their own myths. Lucas’ colours are bright and intense, capturing the spectacle of blossoms, washed out soils, spectacular celestial phenomena and magical gestures. Quickly placed watery areas bear clumping layers of colour. Just as the rainforest produces an abundance of life at high speed, it must carry away all that has passed in the same measure, a highly dynamic becoming and passing that leaves no time to catch one’s breath. Thus, floating plant remains in the river are crusts of colour on Lucas’ canvases. The dynamics of life will push them to the bottom or wash them further. And just as the intoxication of the living takes over those present, so too does the passing proudly step onto the stage of the rainforest spectacle. The contrast between the Ghosts and half–ghosts of the dead to the flowers allows them to shine in their beauty. In this way, flowers, ghosts and the dead appear in contradictory harmony and the impression is created, that death takes great pleasure in beauty in Lucas’ paintings.

In the hut in the middle of the Misiones jungle where Lucas paints, the fauna is dense and populated with endless ants. The beetles are innumerable. Tarantulas fall to the ground with a dull crunch. The chirping of the insects can be so haunting that you could mistake them for ghosts. The rainforest is alive. Lucas is part of this nature, never neutral, sometimes threatened, sometimes ignored, sometimes an intruder. So the hut also offers protection, but you can’t escape nature, scorpions sting with strong poison and those who are not careful find themselves sinking to the bottom of the streams from which the rainforest generates its glow.

Lucas Pertile grew up on the banks of a dark river, the Rio Negro. The Rio Negro is one of the largest tributaries in the world with an enormous mass of water, it flows as a tributary into the Amazon in northern Brazil. It carries black water from a marshy bottom with a nauseating smell, it is inhabited by tough fish with sharp scales that groan when you catch them. Fish that look like they come from prehistoric times. As a child, Lucas had to use a machete to make his way through the dense undergrowth on its banks. Since the age of five, he swam in the murky water that flowed past his house. At the same age, he crossed the river on a tree trunk that his brother had cut down shortly before. He ate water hyacinths. He raised a monkey. At ten, he went fishing with his friends and slept under the stars or in improvised shelters made of bark and branches that protected him from the tropical night.

His grandfather was a painter and his studio had been a familiar place for Lucas since childhood. The grandfather’s studio was a magical place to which not everyone had access, but which had such a strong attraction for Lucas that he never wanted to leave it as a child. His grandfather gave him pencils and let him copy his own pictures. He was a gruff man who found his calling as an artist early on. The art school in Resistencia, Chaco, bears his name: Alfredo Pertile. His grandmother grew flowers, and anyone who knows the life story of the writer Horacio Quiroga, who also had a refuge in Misiones at the beginning of the 20th century, knows that besides countless ants, there is an inordinate force of rainforest capture that makes every flower cultivation a self–sacrificing odyssey. Therefore it is obvious that the spirit of the Pertile family is linked to the flaring of flowers and wild tendrils of plants, and so it is logical that the hut in Misiones in the middle of the rainforest is the source of inspiration for his painting.

The evening light shines over the treetops of the rainforest like burning sparks. Whoever watches the videos on Lucas’ Instagram account shudders at the beauty of this strange natural spectacle. It is accompanied by an ever–present buzzing, as if the insect world were the actual body of nature, invisible but wide awake. The immediate impression is that the rainforest is living under high tension, living for itself, looking inwards with all its creatures on their own, hunt, rest, screaming and seeking other creatures. They act in a hidden way. The individual human being is drawn into this web of life as if into quicksand. Urban realities, human action and communication are only one variation among hundreds of thousands in this mesh. But even here cracks are appearing. Human intrusion into almost all habitats of the world is also taking its toll here. The beautiful jaguar is not the only creature whose species is pushed to the brink of extinction. Through the opening in the foliage, through strands of lianas, one can see out of the inner, intimate capsule of the rainforest in Lucas’ paintings to river mouths, sea accesses, to navigable passages. These are the gateways of human civilisation, eyed suspiciously through the tangle of vegetation, vicariously by the apes in his paintings. But the animal creatures are still playing their own mythical game in the body of the rainforest, occasionally swallowing Lucas inside as their equal.

Lucas’ paintings tell of the wilderness, they describe the living wilderness, with agitated, sometimes strongly gestural traces of painting. Everything seems to be in motion, the leaves seem dynamic like horses, the horses wild like a storm and the monkeys seem to be secretly trying out their own society among themselves, making their own coalitions, telling their own myths. Lucas’ colours are bright and intense, capturing the spectacle of blossoms, washed out soils, spectacular celestial phenomena and magical gestures. Quickly placed watery areas bear clumping layers of colour. Just as the rainforest produces an abundance of life at high speed, it must carry away all that has passed in the same measure, a highly dynamic becoming and passing that leaves no time to catch one’s breath. Thus, floating plant remains in the river are crusts of colour on Lucas’ canvases. The dynamics of life will push them to the bottom or wash them further. And just as the intoxication of the living takes over those present, so too does the passing proudly step onto the stage of the rainforest spectacle. The contrast between the Ghosts and half–ghosts of the dead to the flowers allows them to shine in their beauty. In this way, flowers, ghosts and the dead appear in contradictory harmony and the impression is created, that death takes great pleasure in beauty in Lucas’ paintings.

In the hut in the middle of the Misiones jungle where Lucas paints, the fauna is dense and populated with endless ants. The beetles are innumerable. Tarantulas fall to the ground with a dull crunch. The chirping of the insects can be so haunting that you could mistake them for ghosts. The rainforest is alive. Lucas is part of this nature, never neutral, sometimes threatened, sometimes ignored, sometimes an intruder. So the hut also offers protection, but you can’t escape nature, scorpions sting with strong poison and those who are not careful find themselves sinking to the bottom of the streams from which the rainforest generates its glow.

Installation Views

×

![]()

Works