Marianna Ignataki: The Hole : Verena Kerfin Gallery, Köthener Strasse 28, Berlin 10963

Past

exhibition

Overview

Every Angel is terrible - on MARIANNA IGNATAKI’s drawings

The grotesque body, writes Michael Bakhtin, ignores the smooth surface that closes off the body and delimits it as single and complete. The inside and the outside mix, the boundaries merge, and a transition from life to death, from death to life seems equally conceivable.

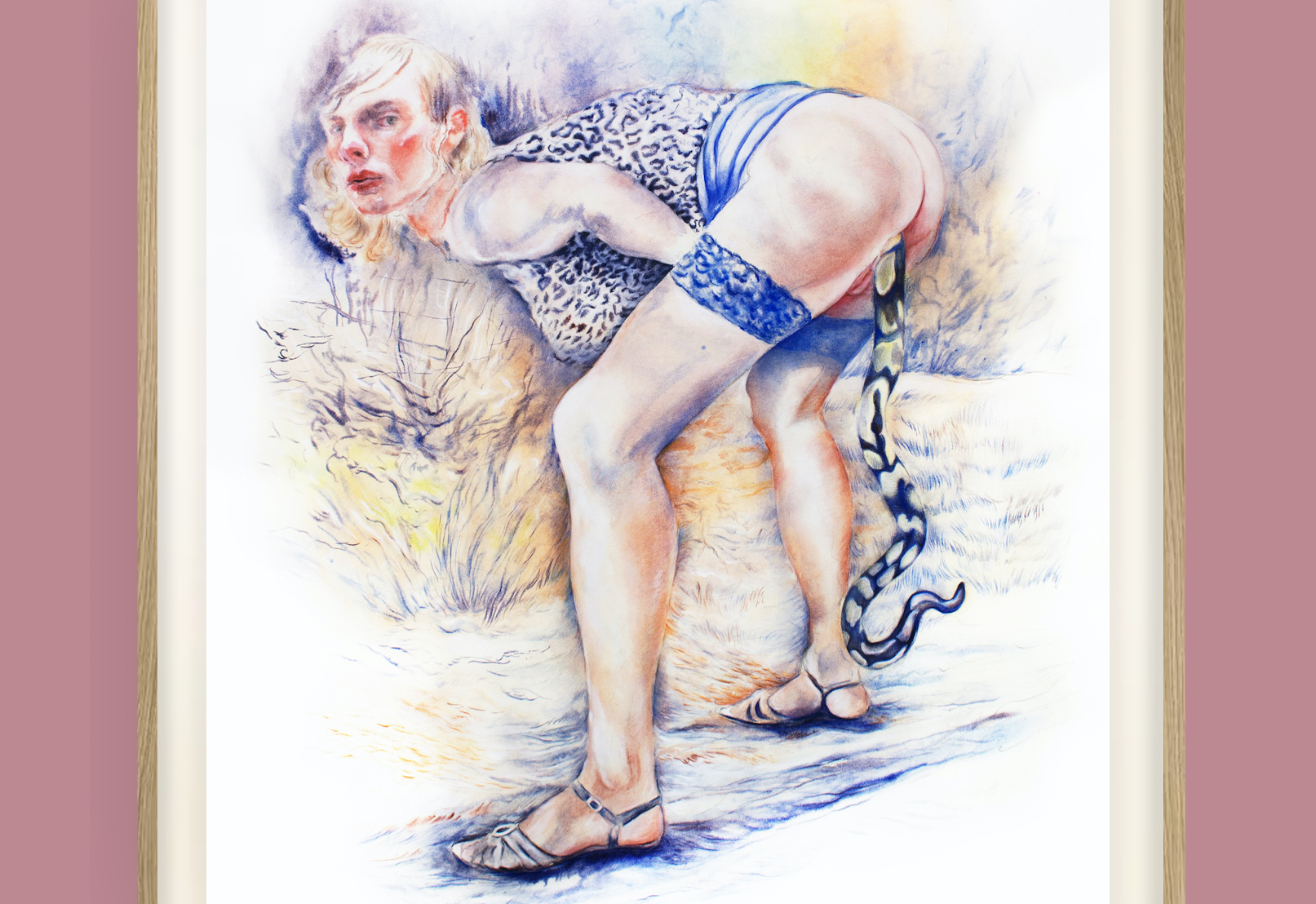

Marianna Ignataki's drawings and watercolors lead us into an intermediate realm, a zone of the poisoned beauty of external appearances, where a bewitching cooing resounds, where a heavy perfume befuddles the senses and where artfully liquid colors elegantly beguile us. A zone of intoxication, seduction and disturbance opens up like a crack in reality, from which a strange melody resounds, like sirens luring Odysseus tied to the mast. Androgynous figures lounge around, lolling self-consciously or plainly arrogantly, leering or simply surveying the viewer, reptilianly lambent.

This aesthetic zone is certainly art-historically mined terrain, a terrain that ranges from the wondrous Garden of Bomarzo of the Italian 16th century to the nervous, sensitive, spiritualized, and thus also turgid creations of Symbolism to the well-known enigmatists of the 20th century, the apologists of the dream and the painful clarity of the subconscious, the disciples of the irrational. In her interpretation of these idioms, however, Ignataki is wise enough to listen to her own voices and finds specific motifs, sounds and a cast of characters that we would follow unconditionally and without hesitation into the sweet abyss.

The hair grows out of their mouths, is held trophy-like in the hand - or rather like an ancient Greek "apotropeion" - a magical defensive object that is supposed to protect against mischief and the evil eye, demonstratively stretched out towards the viewer's eye.

When Ignataki returned to Europe from China, she had kilos of wig hair in her luggage. She also uses it to make sculptures whose idol-like presence appeals to the power of the uncanny. Dark beings - which seem corporeal and otherworldly at the same time. Ancient idols that seem to demand total obedience, discipline and submission.

The trichophagous figures in the drawings are agents of seduction, posing and straddling the gaze, their cold eroticism glowing from within, illuminating the artist's sheets as if by a phosphorizing light ignited beneath her skin.

The fine-curly hair gently streams from within the protagonist, not an eruptive vomit, rather a moderate ripple than a gush. A grotesque-animalistic atavism.

Mary Magdalene, the biblical penitent, wore a garment of hair; in some representations, such as Riemenschneider's famous sculpture, her entire body is a single fur.

A reflection of the creaturely in the garb of the finely chiseled youths and young women who proudly display that which brings pure horror, disgust, wonder to our faces like a cloud of glitter makeup on a forehead heated by the exertion of pleasure. Rilke says that the beautiful is nothing but the beginning of the terrible...

The dissonant, ambiguous concept of beauty of Romanticism found its iconic manifestation in the snake's head of Medusa, and when in Ignataki a snake writhes out of a rectum or its tongue hangs lasciviously from the mouth of a dandy, these are the ironic echoes of a beautiful-terrible Medusa-ness turned into the present. And in this force field we exist unredeemed and hoping with all our poses and our desires.

Jan-Philipp Fruehsorge, Juli 2021

The grotesque body, writes Michael Bakhtin, ignores the smooth surface that closes off the body and delimits it as single and complete. The inside and the outside mix, the boundaries merge, and a transition from life to death, from death to life seems equally conceivable.

Marianna Ignataki's drawings and watercolors lead us into an intermediate realm, a zone of the poisoned beauty of external appearances, where a bewitching cooing resounds, where a heavy perfume befuddles the senses and where artfully liquid colors elegantly beguile us. A zone of intoxication, seduction and disturbance opens up like a crack in reality, from which a strange melody resounds, like sirens luring Odysseus tied to the mast. Androgynous figures lounge around, lolling self-consciously or plainly arrogantly, leering or simply surveying the viewer, reptilianly lambent.

This aesthetic zone is certainly art-historically mined terrain, a terrain that ranges from the wondrous Garden of Bomarzo of the Italian 16th century to the nervous, sensitive, spiritualized, and thus also turgid creations of Symbolism to the well-known enigmatists of the 20th century, the apologists of the dream and the painful clarity of the subconscious, the disciples of the irrational. In her interpretation of these idioms, however, Ignataki is wise enough to listen to her own voices and finds specific motifs, sounds and a cast of characters that we would follow unconditionally and without hesitation into the sweet abyss.

The hair grows out of their mouths, is held trophy-like in the hand - or rather like an ancient Greek "apotropeion" - a magical defensive object that is supposed to protect against mischief and the evil eye, demonstratively stretched out towards the viewer's eye.

When Ignataki returned to Europe from China, she had kilos of wig hair in her luggage. She also uses it to make sculptures whose idol-like presence appeals to the power of the uncanny. Dark beings - which seem corporeal and otherworldly at the same time. Ancient idols that seem to demand total obedience, discipline and submission.

The trichophagous figures in the drawings are agents of seduction, posing and straddling the gaze, their cold eroticism glowing from within, illuminating the artist's sheets as if by a phosphorizing light ignited beneath her skin.

The fine-curly hair gently streams from within the protagonist, not an eruptive vomit, rather a moderate ripple than a gush. A grotesque-animalistic atavism.

Mary Magdalene, the biblical penitent, wore a garment of hair; in some representations, such as Riemenschneider's famous sculpture, her entire body is a single fur.

A reflection of the creaturely in the garb of the finely chiseled youths and young women who proudly display that which brings pure horror, disgust, wonder to our faces like a cloud of glitter makeup on a forehead heated by the exertion of pleasure. Rilke says that the beautiful is nothing but the beginning of the terrible...

The dissonant, ambiguous concept of beauty of Romanticism found its iconic manifestation in the snake's head of Medusa, and when in Ignataki a snake writhes out of a rectum or its tongue hangs lasciviously from the mouth of a dandy, these are the ironic echoes of a beautiful-terrible Medusa-ness turned into the present. And in this force field we exist unredeemed and hoping with all our poses and our desires.

Jan-Philipp Fruehsorge, Juli 2021

Installation Views

×

![]()

×