Toby Ursell: Park Bench Paintings : Verena Kerfin Gallery, Köthener Strasse 28, Berlin 10963

Past

exhibition

Overview

Toby Ursell – Park Bench Paintings

Toby Ursell (b. 1981, Cheltenham) belongs to that crew o’ British painters who don’t treat a picture like a sealed box, but like a stage what can change its act. He trained in Cardiff (BA, 2003) and London (MA, Wimbledon College of Art, 2010), works outta London, and has shown in Berlin (“Oyl Paintings,” BARK Berlin Gallery, 2021) and in London (“A tale told by an idiot…,” Deptford Does Art, 2020). His works sit in private collections, and he’s been sailin’ with Verena Kerfin Gallery for some years now.

All hands on deck!

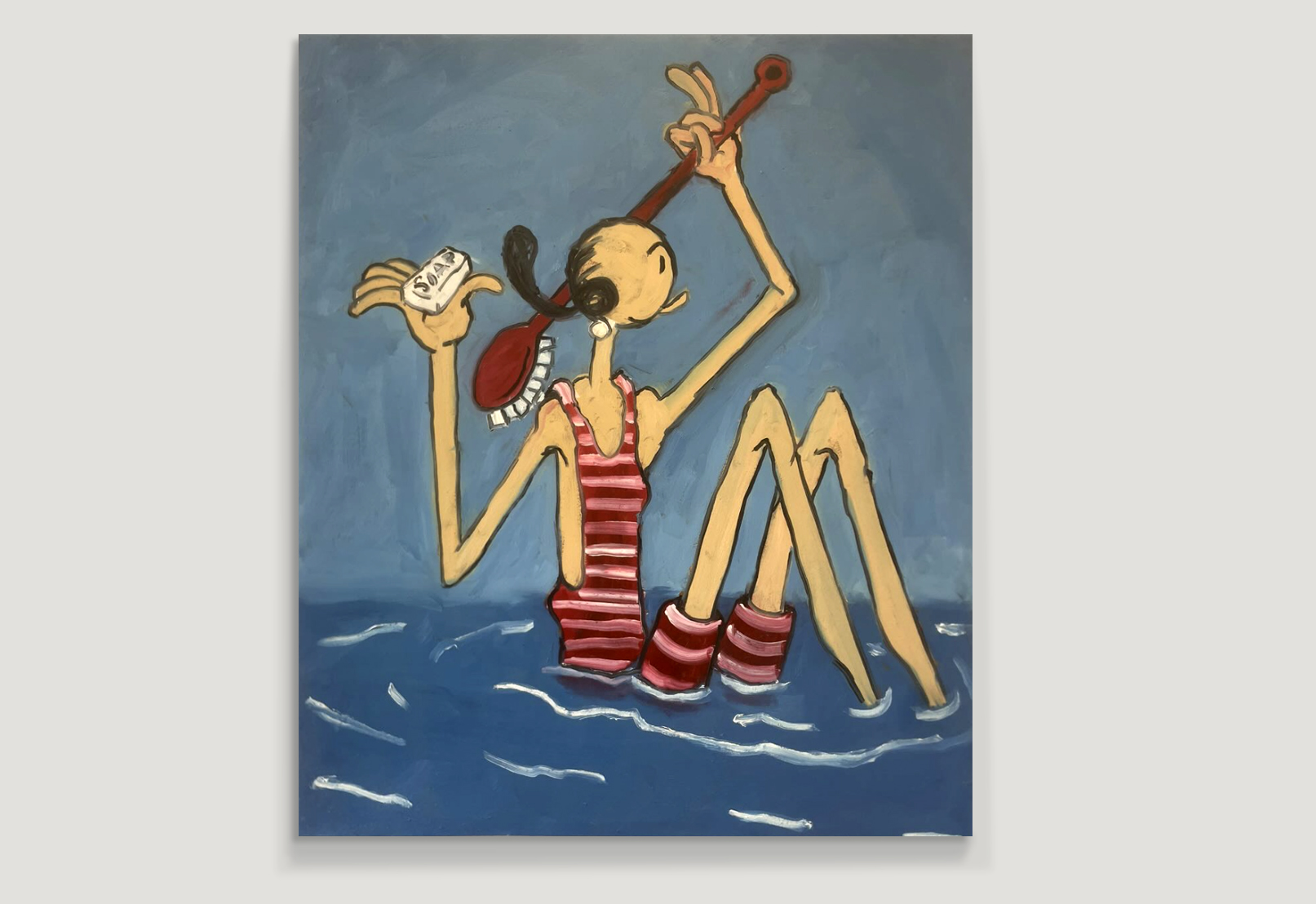

“Park Bench Paintings” hoists the humble, funny-ordinary park bench as its startin’ point. One drawin’—Olive Oyl at both far ends of a near-endless bench—gets painted clean around the room as a wall-frieze. Perched right on the bench’s seat-planks sit the canvases: spinach cans with flowers, coffee pots, bath-time Olive, Popeye & Olive, and more. The bench becomes a carrier for pictures, a stage for figures, and a cheeky comment on how shows are hung. Instead o’ the neutral White Cube, these paintings sit on a bench—neighbors to picnics, chitchat, and waitin’ around—a social map where art bumps elbows with daily life.

Spinach an’ suchlike.

Ursell’s small-to-middlin’ oils haul up things from a “between-world”: not heroic, not just decorative—but loaded with cultural echoes. A spinach can (SP) turns into a vase: an industrial tin turned flower-holder, a hybrid of product and old-school still life. Since the 17th century, still lifes been mirrors for time, ownership, an’ bourgeois order. Here they morph into a comic bit: the market item blooms but stays a can—label, brand, ad surface and all. That’s his soft anarchism: he don’t swap one thing for another; he overlays meanings—like a collage done in oil.

And spinach—well now—that summons a long-running pop tale: Popeye and the wonder-greens. Folks once claimed spinach was packed with iron on account o’ some decimal mishap; truth is, early explanations leaned more toward Vitamin A power. The iron yarn’s been trimmed back, but the cultural punch remained: kids did, in fact, eat more spinach after Popeye. Culture bites.

The loop, see?

Ursell sets the cycle—comic figure → brand item → nutrition myth → everyday object—against the museum’s high deck. Those “SP” vases are emblem (SP = spinach/Popeye), gag (flowers from a can), and tradition (vase) all at once. Side by side along the bench, the small differences start to matter: tonal shifts in the backgrounds, the hitch-and-tug between lettering and painterly skin, and the brush keepin’ contour from color—now sharp like a cartoon, now smeared and buttery.

Olive, ya elegant stringbean.

Pickin’ Olive Oyl—introduced in E. C. Segar’s “Thimble Theatre” in 1919, later world-famous alongside Popeye—is a neat bit o’ sense. She ain’t a classic heroine—more a wiry, willful, funny stretch of a person: a line character through and through. Long limbs, the hair-knot, big shoes—drawn in elastic contours that jump nice to a wall. When she enters Popeye’s world in 1929, the strip’s balance shifts. Ursell echoes that: secondary and main, décor and center, frame and picture get shuffled in the room.

From stem to stern.

Olive sits at both ends. Start and finish, guardin’ the display. This doubling knocks the tyranny o’ the “center” off its peg. The bench becomes a time-line: between left-side Olive and right-side Olive, the tale of the pictures unrolls—a democratic frieze running right along the seat-edge, kept light by a cartoon breeze.

Shiver me timbers (the context’s back).

The White Cube promises “pure” seein’. Ursell’s bench paints the context back in: red slats like horizontal bars, a dusty ground strip like a bit of park path, and a big wash o’ blue that thinks “sky” but stays wall. The canvases actually sit on the bench, goin’ half-sculptural: weight, gravity, shadow—the hang turns into a scene of being there together.

Between the paintings, little things sidle in: a scratched-in name, a canvas flipped over, a bottle. These pocket-pebbles give the row its rhythm—breath marks between the songs. They point back to studio life: broodin’, doodlin’, takin’ five, waitin’ it out. The bench becomes a workbench.

Method, plain an’ simple.

Ursell sails between two poles: the cartooning of painting (clear contours, trimmed form, pointed gestures, flat color fields) and the painting of cartoons (grainy color, correction shadows, the visible hand, a hunger for surface). This spread makes the works feel right-now: neither nostalgia gags nor pure form drills, but working pictures that own up to matter (oil, wood, canvas, wall paint) and to cultural traffic (labels, figures, memes).

Let’s stroll, you ’n’ me.

A bench’s an anti-pedestal. Museums lift and isolate; benches invite sittin’ together. There ain’t a “best seat”—the pecking order stays low. In the room, that turns into a flâneur’s walk: you drift along the bench like crossin’ a park. The pictures jaw at each other—SP vase next to kettle, Olive close by Popeye—while Olive pops up again at the end (and the other end), turnin’ witness and partner to the folks lookin’.

Well, blow me down—what fun.

Here’s the “anarchic pleasure”: things get to show their double nature—use-thing and picture-thing, joke and earnest, brand and paint. The painting lands a ground that ain’t living room nor museum but park—a public, poetic space where a bench is enough to set art down, while also askin’ the setup question: Who sets? Where? Why this way?

Talk it over.

Ursell’s figures and vessels start conversations. They tug memories—Saturday comics, labels you copied as a kid, your grandma’s coffee pot, that first picnic. But the painting stays formal-minded: contour versus field, script (SP) versus image, the balance of small sizes in a broad room. With the bench as score-line, the talk keeps its order without losin’ its game: you can hop up, slide over, hold still. So “Park Bench Paintings” becomes a quiet lesson: not the wall text explains the picture, but the arrangement does. Not the neutral white, but the painted surroundings let the works speak. Not distance, but nearness makes ’em plain to see.

That’s me two cents.

In Berlin, Toby Ursell shows how painting can stay in everyday use without turnin’ cheap. He knows his still-life history, the White Cube’s aura, and the engines of pop culture—and he nudges the lot toward humor, gentleness, and a pinch of mischief. Olive watchin’ over the bench ain’t just a nod; it’s a workin’ metaphor for the whole stance—one foot in the canon and one foot off to the side, in cartoon and in paint, in park and in museum.

Toby Ursell (b. 1981, Cheltenham) belongs to that crew o’ British painters who don’t treat a picture like a sealed box, but like a stage what can change its act. He trained in Cardiff (BA, 2003) and London (MA, Wimbledon College of Art, 2010), works outta London, and has shown in Berlin (“Oyl Paintings,” BARK Berlin Gallery, 2021) and in London (“A tale told by an idiot…,” Deptford Does Art, 2020). His works sit in private collections, and he’s been sailin’ with Verena Kerfin Gallery for some years now.

All hands on deck!

“Park Bench Paintings” hoists the humble, funny-ordinary park bench as its startin’ point. One drawin’—Olive Oyl at both far ends of a near-endless bench—gets painted clean around the room as a wall-frieze. Perched right on the bench’s seat-planks sit the canvases: spinach cans with flowers, coffee pots, bath-time Olive, Popeye & Olive, and more. The bench becomes a carrier for pictures, a stage for figures, and a cheeky comment on how shows are hung. Instead o’ the neutral White Cube, these paintings sit on a bench—neighbors to picnics, chitchat, and waitin’ around—a social map where art bumps elbows with daily life.

Spinach an’ suchlike.

Ursell’s small-to-middlin’ oils haul up things from a “between-world”: not heroic, not just decorative—but loaded with cultural echoes. A spinach can (SP) turns into a vase: an industrial tin turned flower-holder, a hybrid of product and old-school still life. Since the 17th century, still lifes been mirrors for time, ownership, an’ bourgeois order. Here they morph into a comic bit: the market item blooms but stays a can—label, brand, ad surface and all. That’s his soft anarchism: he don’t swap one thing for another; he overlays meanings—like a collage done in oil.

And spinach—well now—that summons a long-running pop tale: Popeye and the wonder-greens. Folks once claimed spinach was packed with iron on account o’ some decimal mishap; truth is, early explanations leaned more toward Vitamin A power. The iron yarn’s been trimmed back, but the cultural punch remained: kids did, in fact, eat more spinach after Popeye. Culture bites.

The loop, see?

Ursell sets the cycle—comic figure → brand item → nutrition myth → everyday object—against the museum’s high deck. Those “SP” vases are emblem (SP = spinach/Popeye), gag (flowers from a can), and tradition (vase) all at once. Side by side along the bench, the small differences start to matter: tonal shifts in the backgrounds, the hitch-and-tug between lettering and painterly skin, and the brush keepin’ contour from color—now sharp like a cartoon, now smeared and buttery.

Olive, ya elegant stringbean.

Pickin’ Olive Oyl—introduced in E. C. Segar’s “Thimble Theatre” in 1919, later world-famous alongside Popeye—is a neat bit o’ sense. She ain’t a classic heroine—more a wiry, willful, funny stretch of a person: a line character through and through. Long limbs, the hair-knot, big shoes—drawn in elastic contours that jump nice to a wall. When she enters Popeye’s world in 1929, the strip’s balance shifts. Ursell echoes that: secondary and main, décor and center, frame and picture get shuffled in the room.

From stem to stern.

Olive sits at both ends. Start and finish, guardin’ the display. This doubling knocks the tyranny o’ the “center” off its peg. The bench becomes a time-line: between left-side Olive and right-side Olive, the tale of the pictures unrolls—a democratic frieze running right along the seat-edge, kept light by a cartoon breeze.

Shiver me timbers (the context’s back).

The White Cube promises “pure” seein’. Ursell’s bench paints the context back in: red slats like horizontal bars, a dusty ground strip like a bit of park path, and a big wash o’ blue that thinks “sky” but stays wall. The canvases actually sit on the bench, goin’ half-sculptural: weight, gravity, shadow—the hang turns into a scene of being there together.

Between the paintings, little things sidle in: a scratched-in name, a canvas flipped over, a bottle. These pocket-pebbles give the row its rhythm—breath marks between the songs. They point back to studio life: broodin’, doodlin’, takin’ five, waitin’ it out. The bench becomes a workbench.

Method, plain an’ simple.

Ursell sails between two poles: the cartooning of painting (clear contours, trimmed form, pointed gestures, flat color fields) and the painting of cartoons (grainy color, correction shadows, the visible hand, a hunger for surface). This spread makes the works feel right-now: neither nostalgia gags nor pure form drills, but working pictures that own up to matter (oil, wood, canvas, wall paint) and to cultural traffic (labels, figures, memes).

Let’s stroll, you ’n’ me.

A bench’s an anti-pedestal. Museums lift and isolate; benches invite sittin’ together. There ain’t a “best seat”—the pecking order stays low. In the room, that turns into a flâneur’s walk: you drift along the bench like crossin’ a park. The pictures jaw at each other—SP vase next to kettle, Olive close by Popeye—while Olive pops up again at the end (and the other end), turnin’ witness and partner to the folks lookin’.

Well, blow me down—what fun.

Here’s the “anarchic pleasure”: things get to show their double nature—use-thing and picture-thing, joke and earnest, brand and paint. The painting lands a ground that ain’t living room nor museum but park—a public, poetic space where a bench is enough to set art down, while also askin’ the setup question: Who sets? Where? Why this way?

Talk it over.

Ursell’s figures and vessels start conversations. They tug memories—Saturday comics, labels you copied as a kid, your grandma’s coffee pot, that first picnic. But the painting stays formal-minded: contour versus field, script (SP) versus image, the balance of small sizes in a broad room. With the bench as score-line, the talk keeps its order without losin’ its game: you can hop up, slide over, hold still. So “Park Bench Paintings” becomes a quiet lesson: not the wall text explains the picture, but the arrangement does. Not the neutral white, but the painted surroundings let the works speak. Not distance, but nearness makes ’em plain to see.

That’s me two cents.

In Berlin, Toby Ursell shows how painting can stay in everyday use without turnin’ cheap. He knows his still-life history, the White Cube’s aura, and the engines of pop culture—and he nudges the lot toward humor, gentleness, and a pinch of mischief. Olive watchin’ over the bench ain’t just a nod; it’s a workin’ metaphor for the whole stance—one foot in the canon and one foot off to the side, in cartoon and in paint, in park and in museum.

Installation Views

×

![]()

Works

-

Toby UrsellWimpy Contemplates The Sublime, 2020

Toby UrsellWimpy Contemplates The Sublime, 2020 -

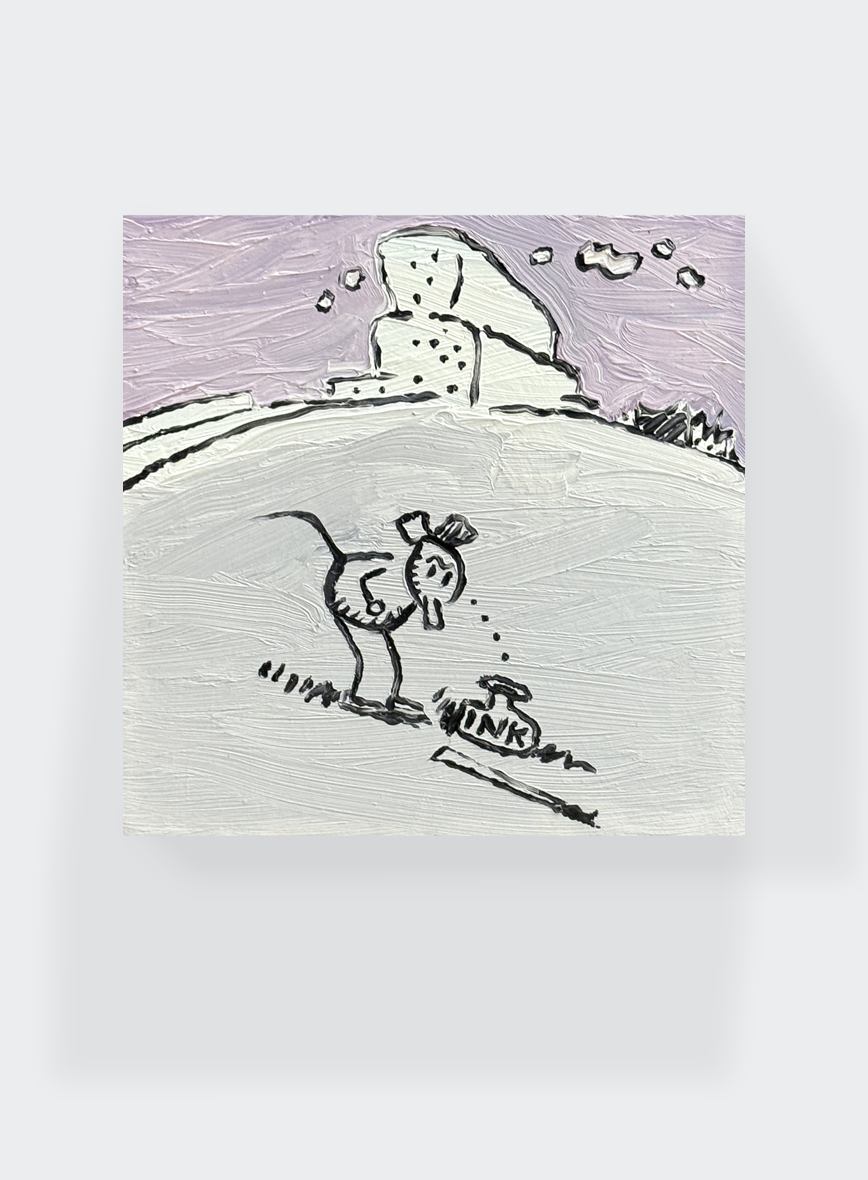

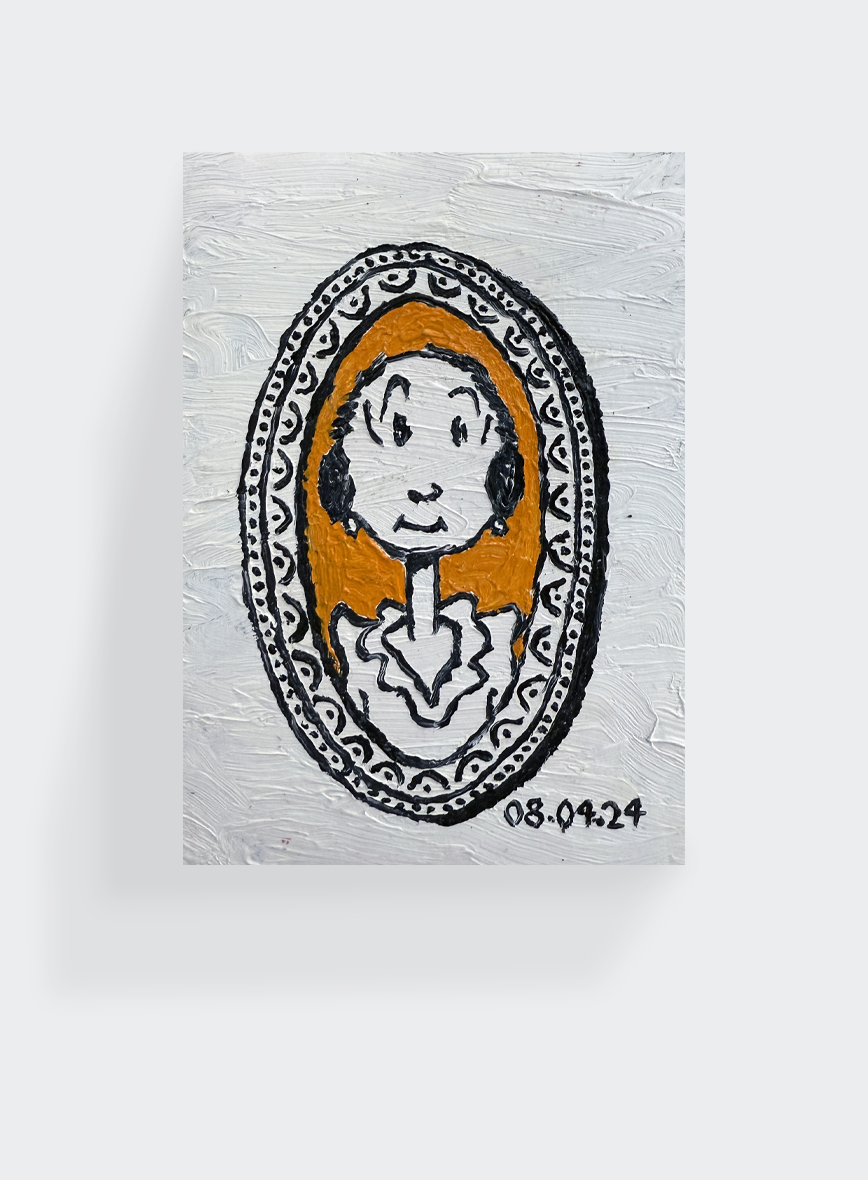

Toby UrsellThinking of Inking (after George Herriman), 2024

Toby UrsellThinking of Inking (after George Herriman), 2024 -

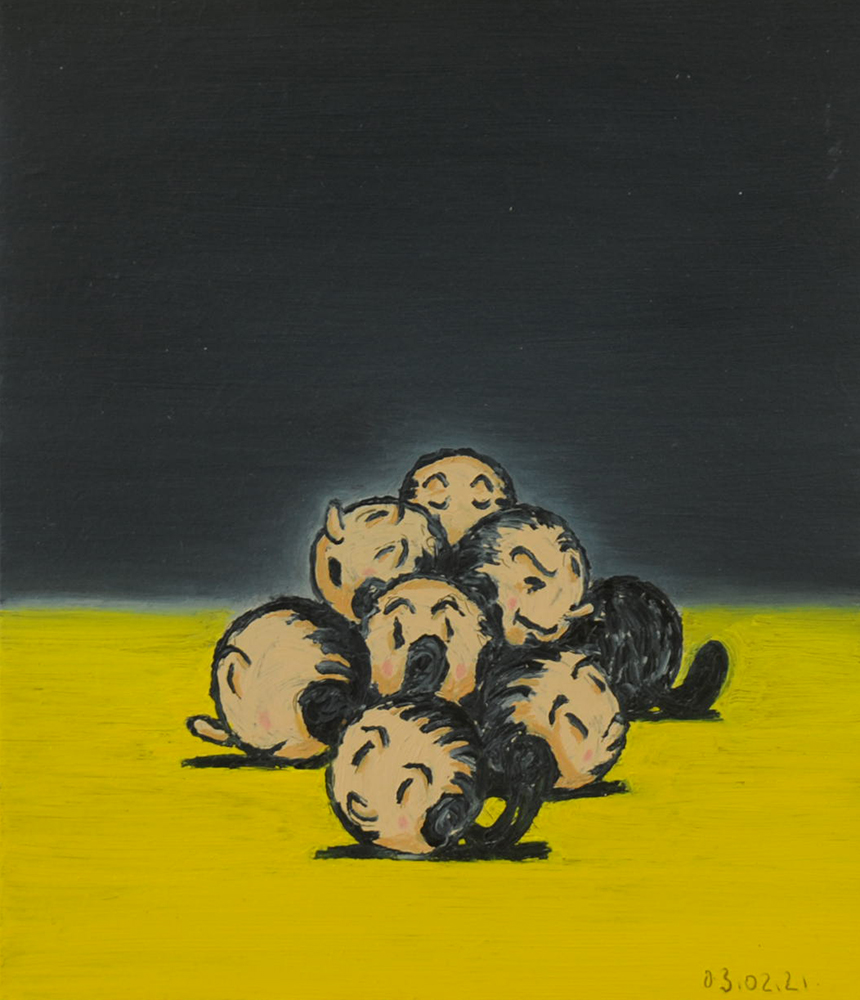

Toby UrsellThe Tormentors, 2021

Toby UrsellThe Tormentors, 2021 -

Toby UrsellThe Apology, 2024

Toby UrsellThe Apology, 2024 -

Toby UrsellThe Apology II, 2024

Toby UrsellThe Apology II, 2024 -

Toby UrsellStarry, Starry Night (The Perseids), 2023

Toby UrsellStarry, Starry Night (The Perseids), 2023 -

Toby UrsellSoap Bar, 2023

Toby UrsellSoap Bar, 2023 -

Toby UrsellThe Lacemaker, 2022

Toby UrsellThe Lacemaker, 2022 -

Toby UrsellThe Kiss, 2024

Toby UrsellThe Kiss, 2024 -

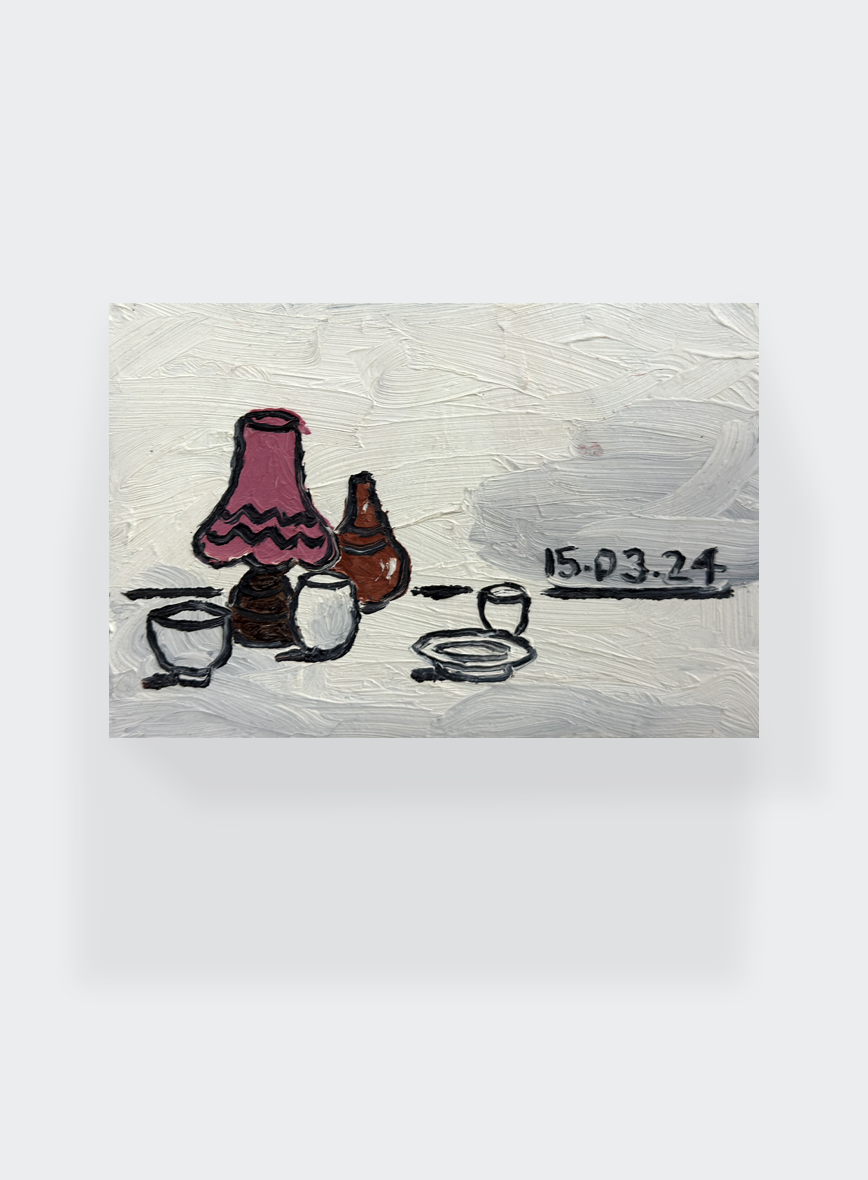

Toby UrsellStill Life, 2024

Toby UrsellStill Life, 2024 -

Toby UrsellThe Gangs All Here, 2023

Toby UrsellThe Gangs All Here, 2023 -

Toby UrsellSt. Remy, 2023

Toby UrsellSt. Remy, 2023 -

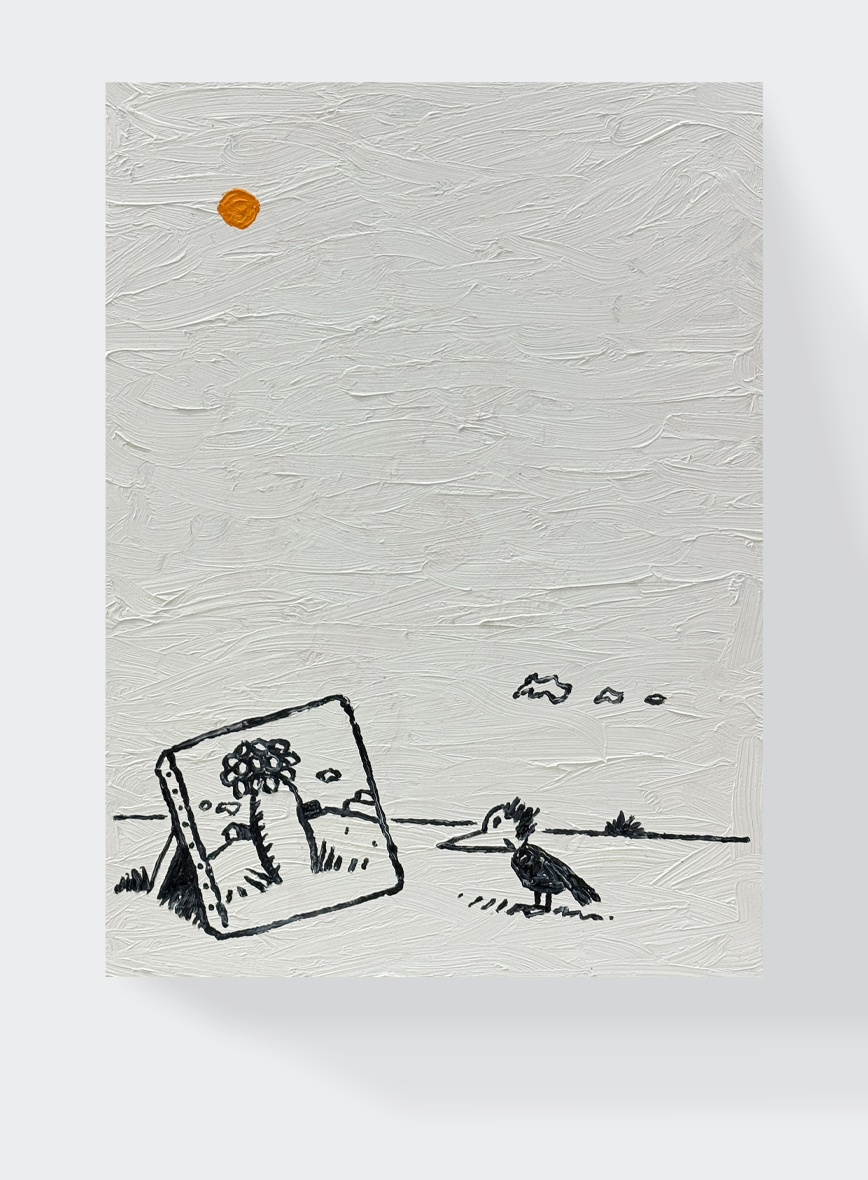

Toby UrsellEdge of Town, 2024

Toby UrsellEdge of Town, 2024 -

Toby UrsellDawn, 2014

Toby UrsellDawn, 2014 -

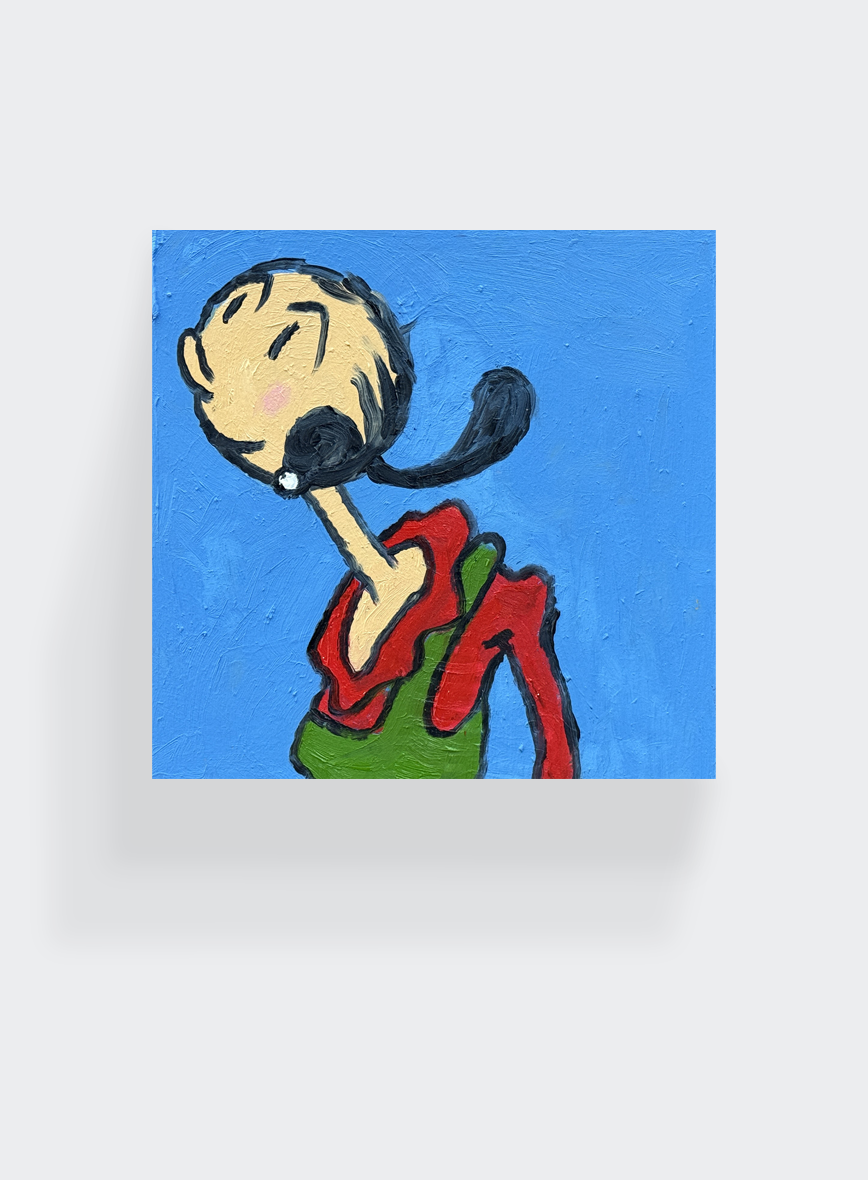

Toby UrsellSmall Oyl, 2023

Toby UrsellSmall Oyl, 2023 -

Toby UrsellContent with Her Lot, 2023

Toby UrsellContent with Her Lot, 2023 -

Toby UrsellSliders, 2024

Toby UrsellSliders, 2024 -

Toby UrsellRiding Around, 2022

Toby UrsellRiding Around, 2022 -

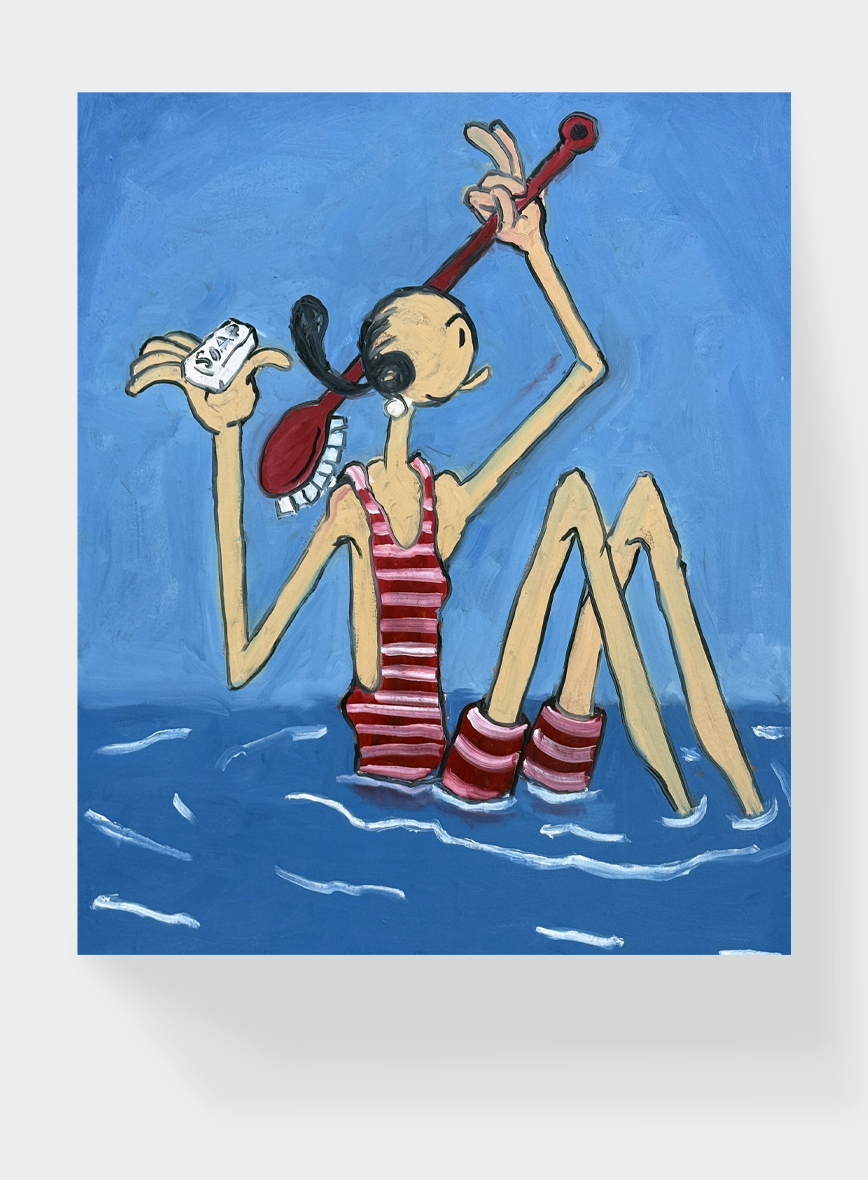

Toby UrsellBather, 2024

Toby UrsellBather, 2024 -

Toby UrsellOyl Painting, 2024

Toby UrsellOyl Painting, 2024 -

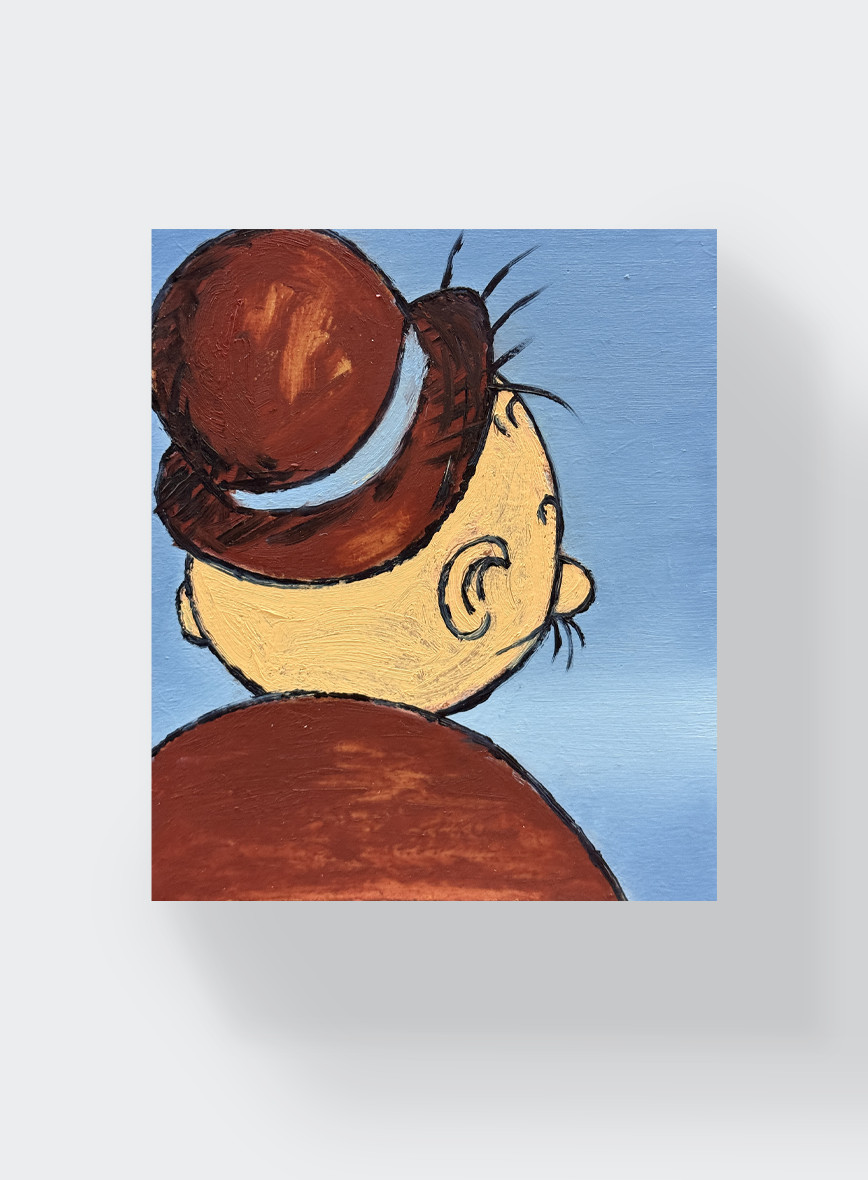

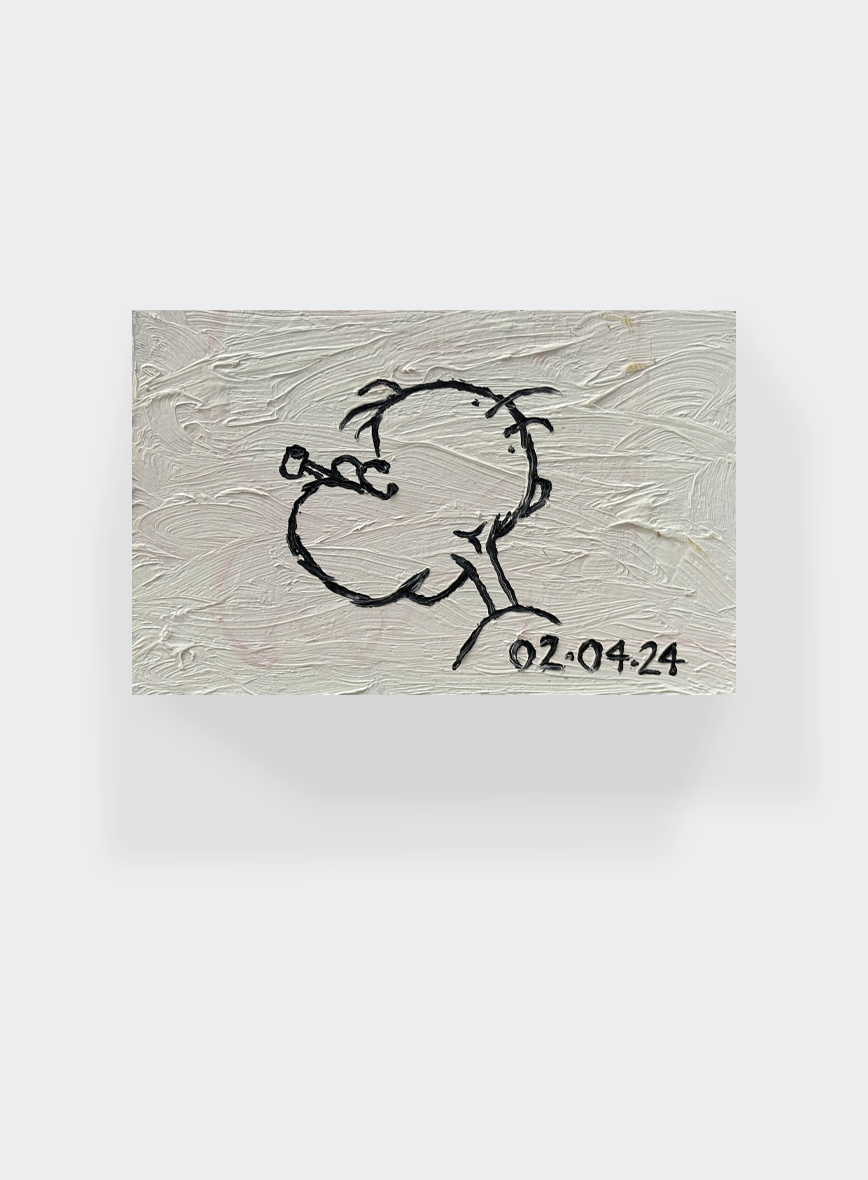

Toby UrsellBack of Head, 2024

Toby UrsellBack of Head, 2024 -

Toby UrsellOrt Kritic, 2024

Toby UrsellOrt Kritic, 2024 -

Toby UrsellMellow Birds, 2022

Toby UrsellMellow Birds, 2022 -

Toby UrsellImpression Soleil Levant, 2023

Toby UrsellImpression Soleil Levant, 2023 -

Toby UrsellIf These Burgers Should Fall, 2023

Toby UrsellIf These Burgers Should Fall, 2023 -

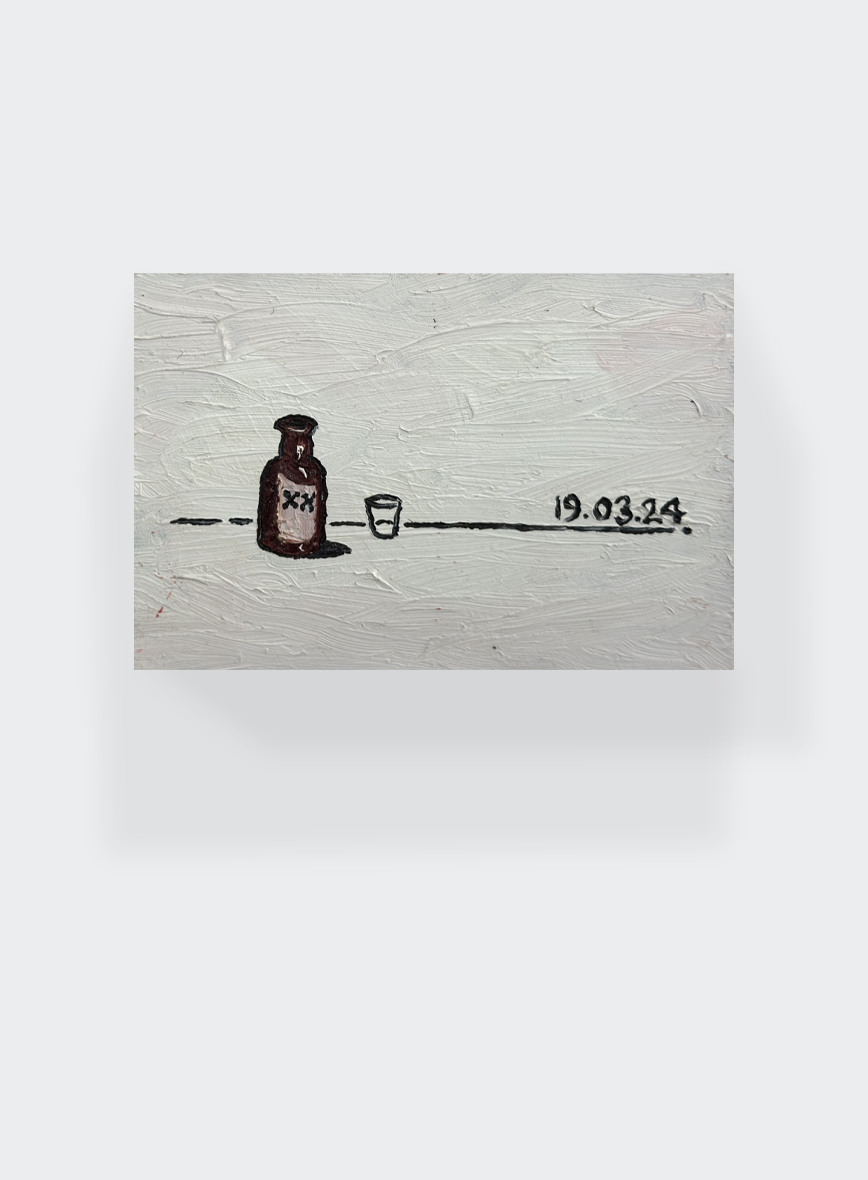

Toby UrsellHorizon, 2024

Toby UrsellHorizon, 2024 -

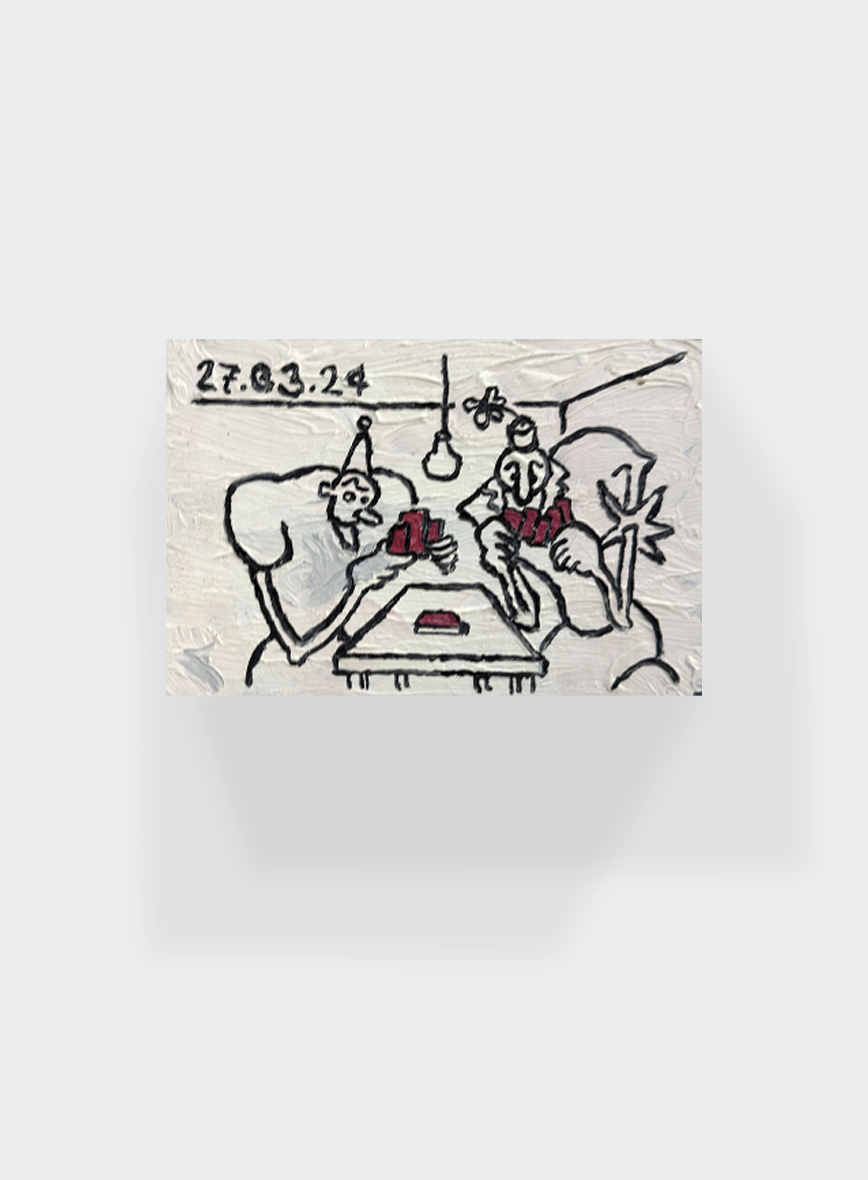

Toby UrsellThe card Players, 2024

Toby UrsellThe card Players, 2024 -

Toby UrsellFlowers for Gauguin, 2024

Toby UrsellFlowers for Gauguin, 2024 -

Toby UrsellBonnard's Burgers, 2023

Toby UrsellBonnard's Burgers, 2023

×