Ondrej Drescher: GAZA, again : Verena Kerfin Gallery, Köthener Strasse 28, Berlin 10963

Past

exhibition

Overview

Why another GAZA exhibition?

Because the attacks haven’t stopped.

Because new names keep appearing.

18,500 dead children in Gaza!

18,500 as of July 2025 -> Washington Post

Gaza – Art as Butterfly Research

In the self-conception of most contemporary artists, art bears no substantive relation to reality—much less to the mission Heiner Müller assigned to it: to render reality ”impossible“. Müller did not mean to ignore reality, nor to beautify it, but to intervene deliberately in its ideological construction. To ”make reality impossible“ means to interrupt, distort, and confront it so profoundly that its presumed naturalness fractures—extracting it from the grip of dominant orders by making its prevailing images and narratives unusable for their original political ends. That is the essence of Müller's notion of resistance: art must never collude with power; it must disrupt language and sabotage authority.

Today, however, many insiders are content with far lesser ambitions. They pontificate in unmoored clichés about their own economic relevance, call themselves “lifespenders” of Berlin, and define their role, with a straight face, as butterfly researchers of ideas: “It’s more like artists are blind butterfly researchers: they catch ideas that no one has been able to name.” Which ideas those might be, they of course decline to specify; but in their certainty lies this promise: “Only later, when the phenomenon becomes tangible, do journalists, scholars, intellectuals, and political actors pick up the thread. Art was already there—as the forerunner into a space others enter later.” This self-satisfied madness can only end in a refusal to face reality, an offensively obvious triviality.

This delusion has spread like a virus. Education becomes secondary; interpretation—however vacuously intellectual—matters only insofar as it does not imperil the sole crucial metric: economic success, the visible performance of “having made it.” Thus even the final stanza of Brecht's Mack the Knife:

“For some are in darkness

And others in the light.

You see those in the light;

Those in the darkness, you do not.”

is no longer read as a radical indictment of violence or a critique of societies that reward those who walk over bodies—literal or moral. Instead, it's sentimentalized into something diffuse and human: “The poem expresses something human, a figure that becomes visible in the light, or remains invisible.” Here, not only does a misreading come to an end; it inaugurates the smooth transition into an intellect-free grandeur—self-defined by a Berlin artist of supposed “world class” in his own exhibition text.

It is therefore hardly surprising that a Berlin painter, unbothered by any real confrontation, paints himself on an annual French vacation as a suffering Christmas tree with a thousand droplets of blood in a knitted sweater, a folkloric emblem of weltschmerz born solely from the inability to perceive any concrete manifestation of reality—embraced in traditional-German introspection, even while his domestic factories deliver drones and artillery shells abroad to engineer a ceaseless man-made blood rain.

The German artist scene is not merely intellectually impoverished—it ostentatiously cultivates that poverty. They resemble pimps basking in glitz and bling-bling—not to signify substance, but to charm, fully aware that no one truly needs them.

Then there is another measure: Fernando Botero, in 2004, aboard a plane to Paris, read reports of torture and abuse by US soldiers at Abu Ghraib. He did not respond with metaphor or a decorative “aesthetic gesture,” but with real images. For a year, he drew and painted what he had seen and read. His aim: to sear those images irreversibly into the world’s memory—just as Picasso’s Guernica became the iconic symbol of aerial terror. Botero offered the full Abu Ghraib series to US museums free of charge, but only under the condition of permanent exhibition. Initially refused, the series later found a home at the University of California.

Not only does the society we inhabit suppress every renewal and reject any open dialogue—but the art world also submits willingly. Minds are surrendered at the entrance to the consumption paradise, churned out as visual disposable goods that no one needs. Artists paint scenes they claim were inspired by “sitting by the water and feeling one with it.”

Meanwhile, in Gaza, thousands of children are buried under collapsing buildings pounded by air bombardments—deliberate or random. Children are taken out by snipers. Cars filled only with children are riddled for hours, even after the Palestine Red Crescent Society pleads for a ceasefire. The images flooding in are soaked in blood-red suffusion—yet people choke on the endless monologue of the trivial, preening as butterfly catchers and thinkers about light, preferably in a knitted sweater with more tear-shaped drops of blood than the Jesus in the village church of Kiss-My-Ass-Nowheresville ever had.

Anyone who, in the face of this reality, remains silent—or finds refuge in harmless metaphors and theatrical gestures—has effectively exited the realm of art and entered a brutal devolution that enables mass murder, rather than rendering that reality impossible.

Text: Ondrej Drescher, Aug. 2025

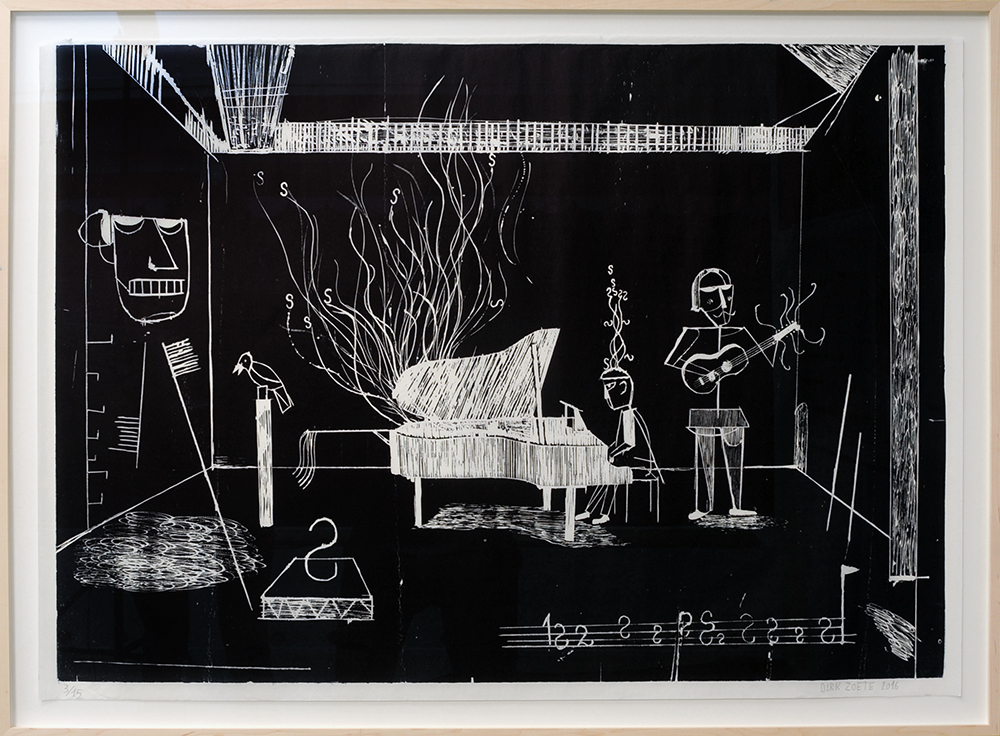

Installation Views

×

![]()

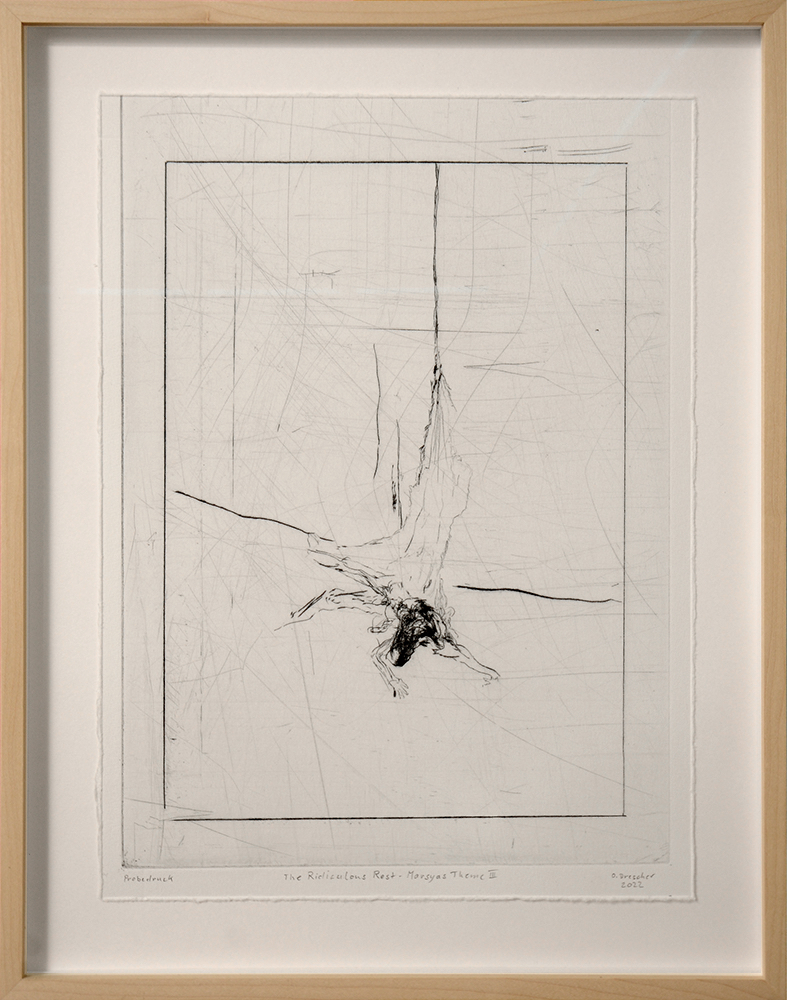

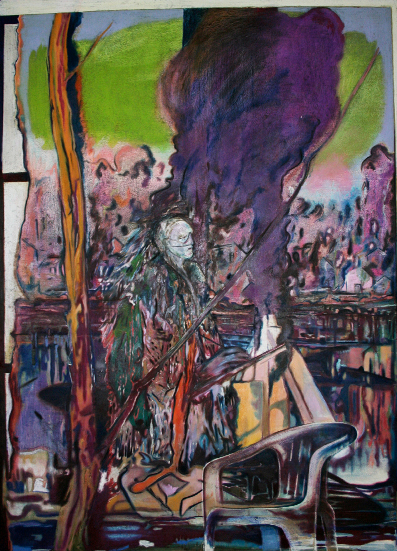

Works

-

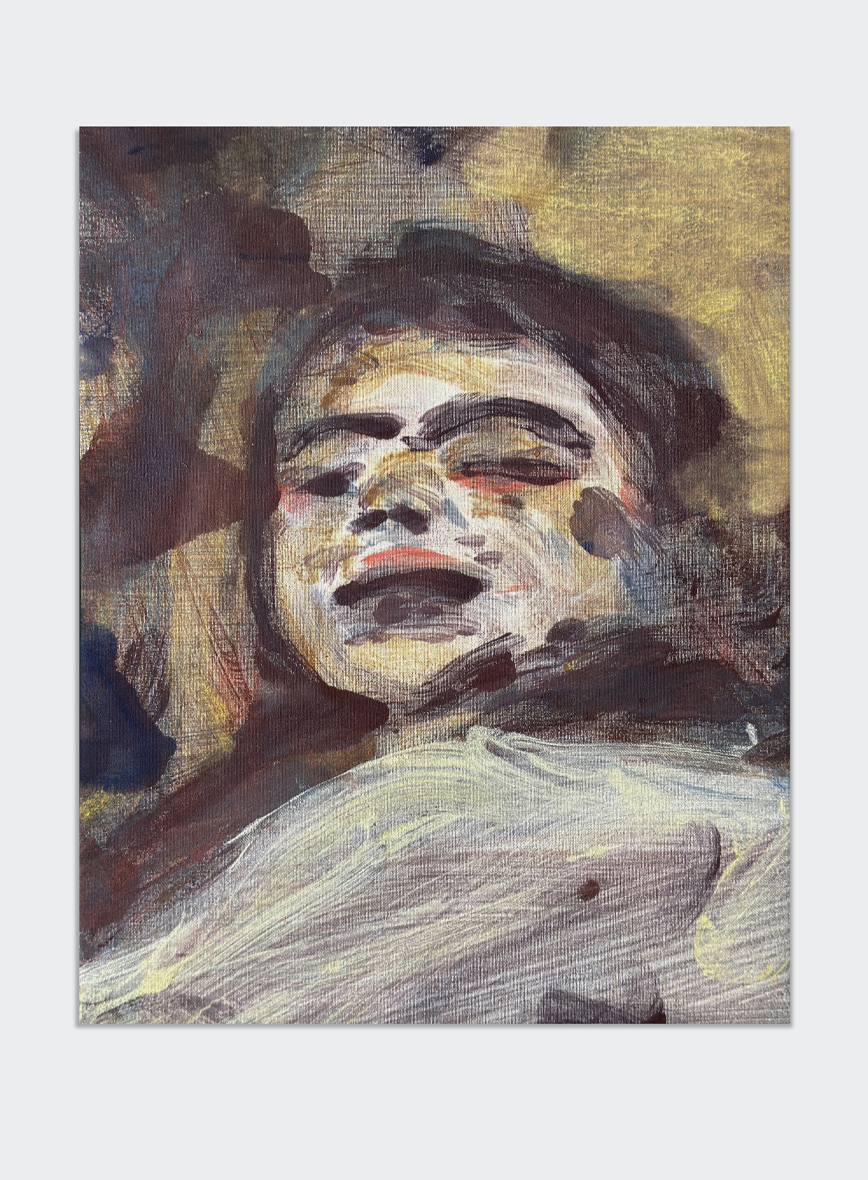

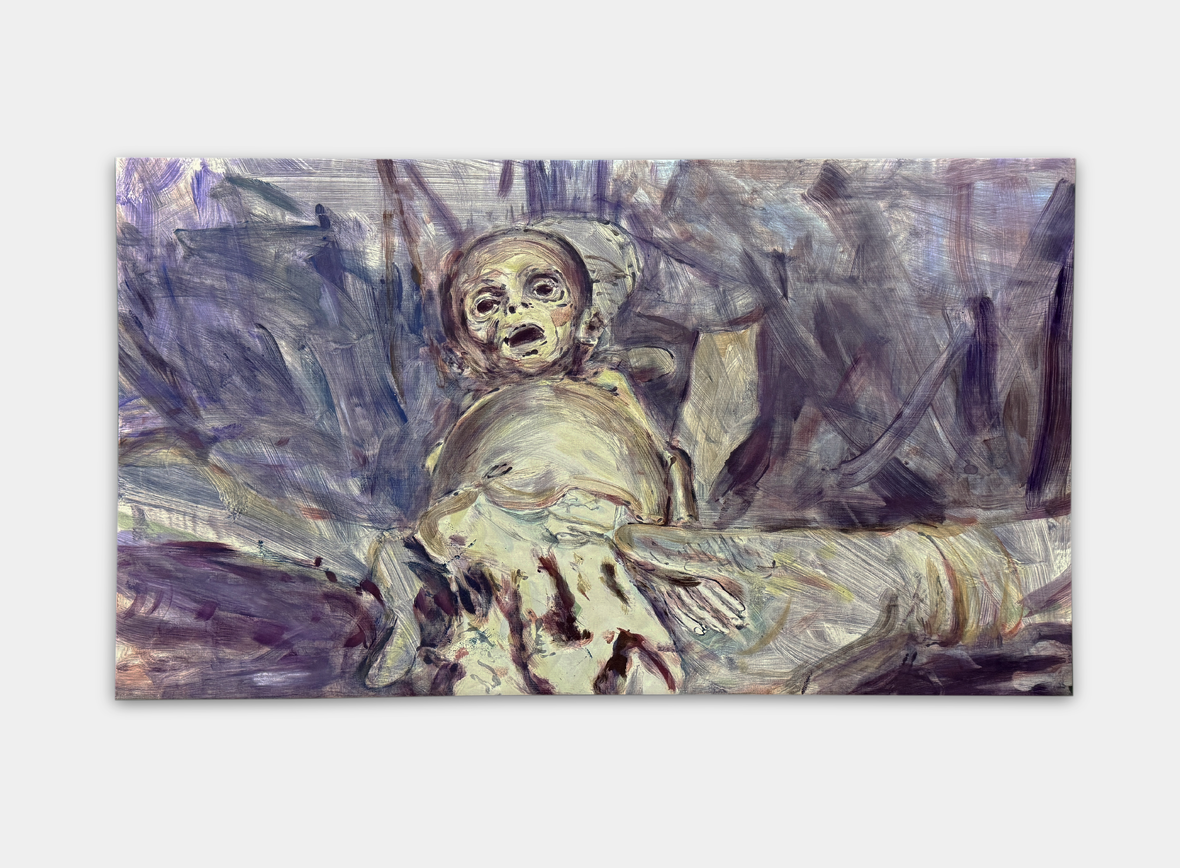

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 1, 2025

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 1, 2025 -

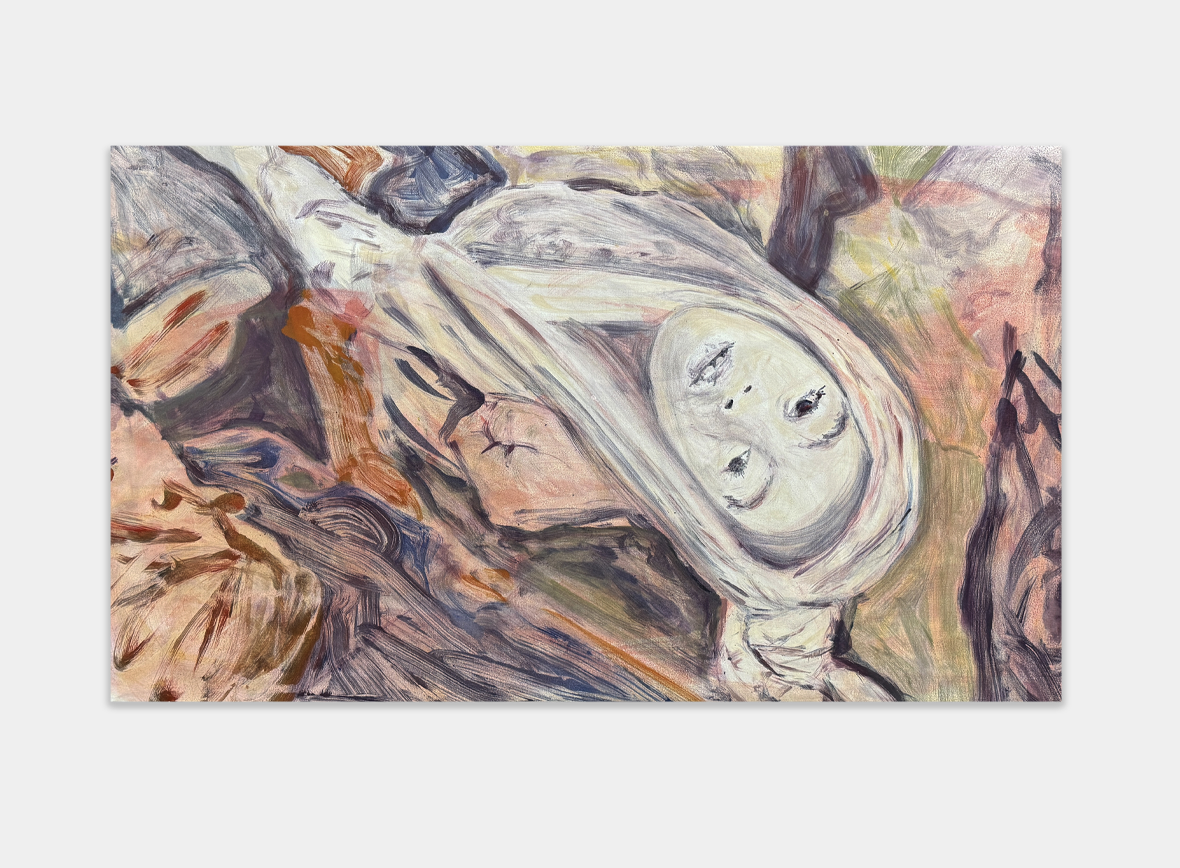

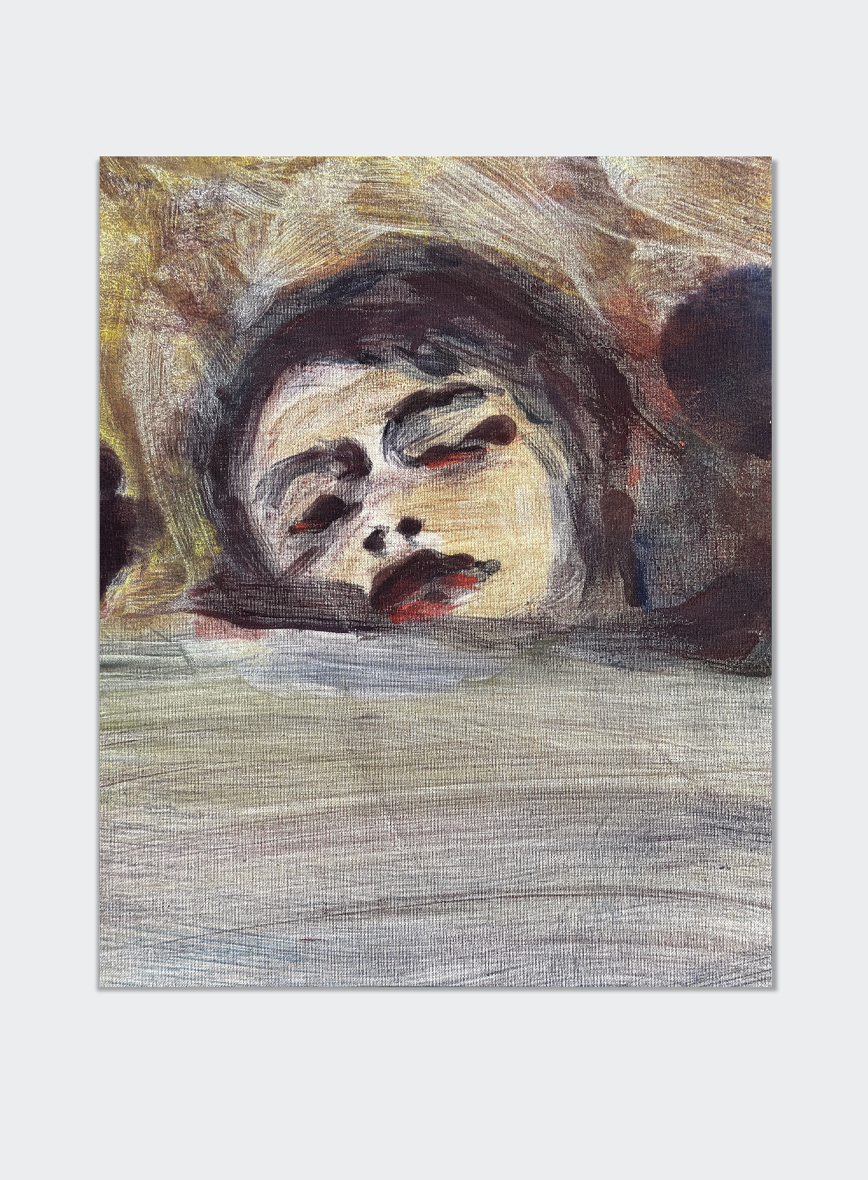

Ondrej DrescherShroud for One of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 1, 2025

Ondrej DrescherShroud for One of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 1, 2025 -

Ondrej DrescherShroud for One of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 2, 2025

Ondrej DrescherShroud for One of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 2, 2025 -

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 7, 2025

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 7, 2025 -

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 5, 2025

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 5, 2025 -

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 6, 2025

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 6, 2025 -

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 4, 2025

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 4, 2025 -

Ondrej DrescherTwo of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 1, 2025

Ondrej DrescherTwo of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 1, 2025 -

Ondrej Drescher2 out of 16k Children Bombed to Death in Gaza / 2024, 2024

Ondrej Drescher2 out of 16k Children Bombed to Death in Gaza / 2024, 2024 -

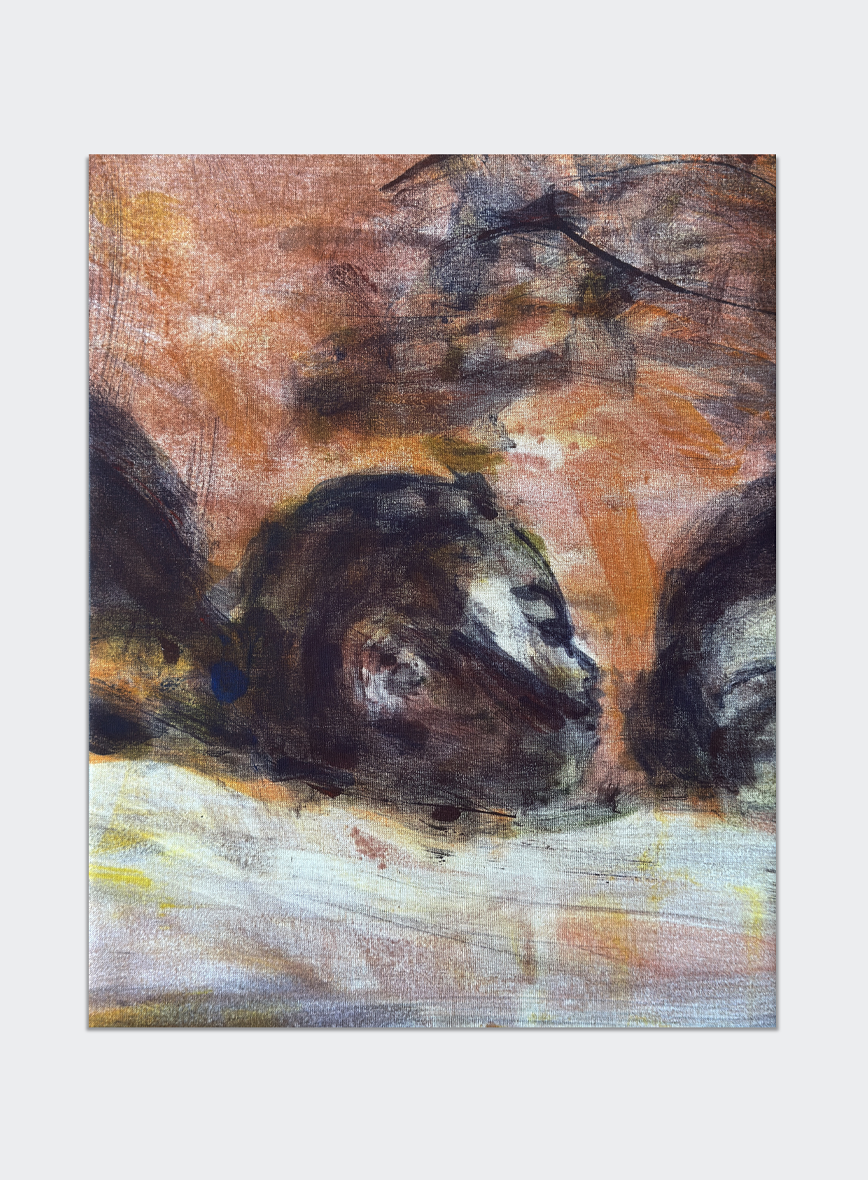

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 2, 2025

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 2, 2025 -

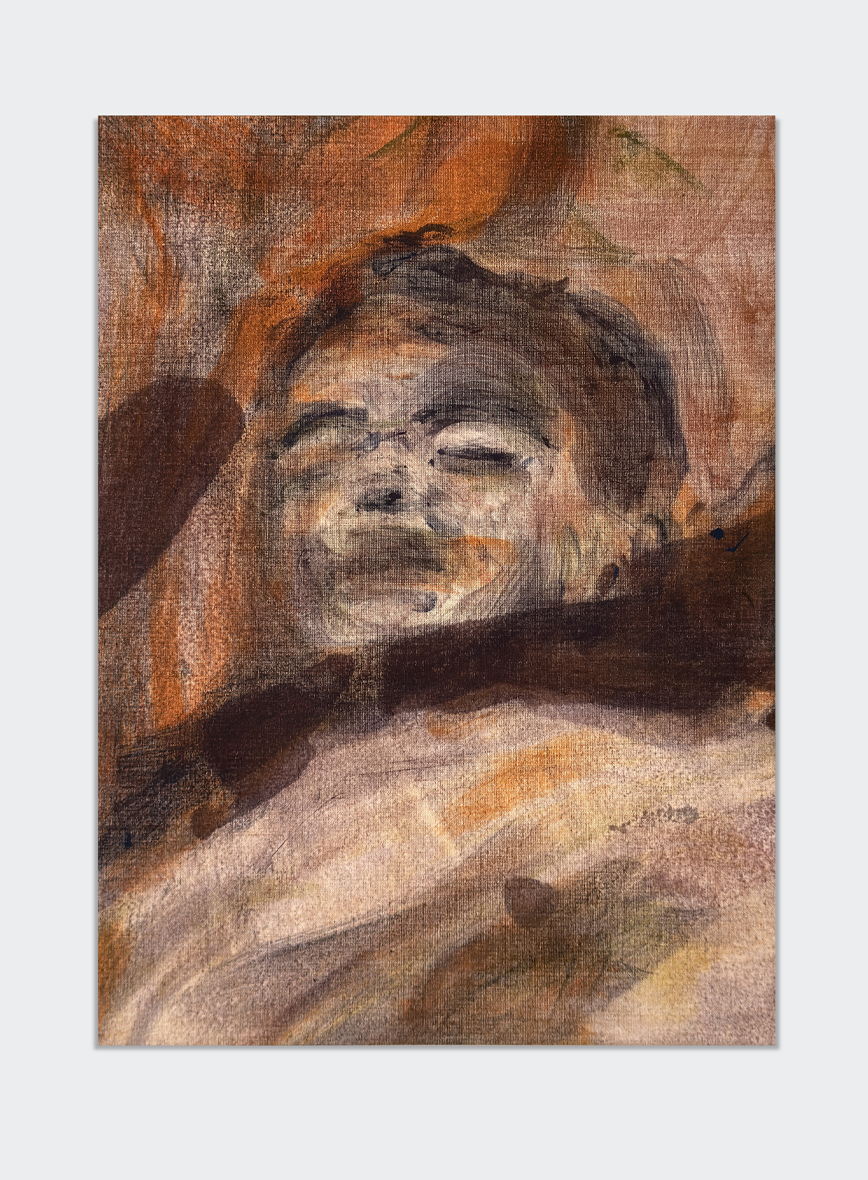

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 3, 2025

Ondrej DrescherOne of the 28 Children Killed Daily by the IDF (18,500 as of July 2025) - 3, 2025

×