Kerstin Pfefferkorn: Knabenmorgenblütenträume : Verena Kerfin Gallery, Köthener Strasse 28, Berlin 10963

Past

exhibition

Overview

The future does not exist yet.

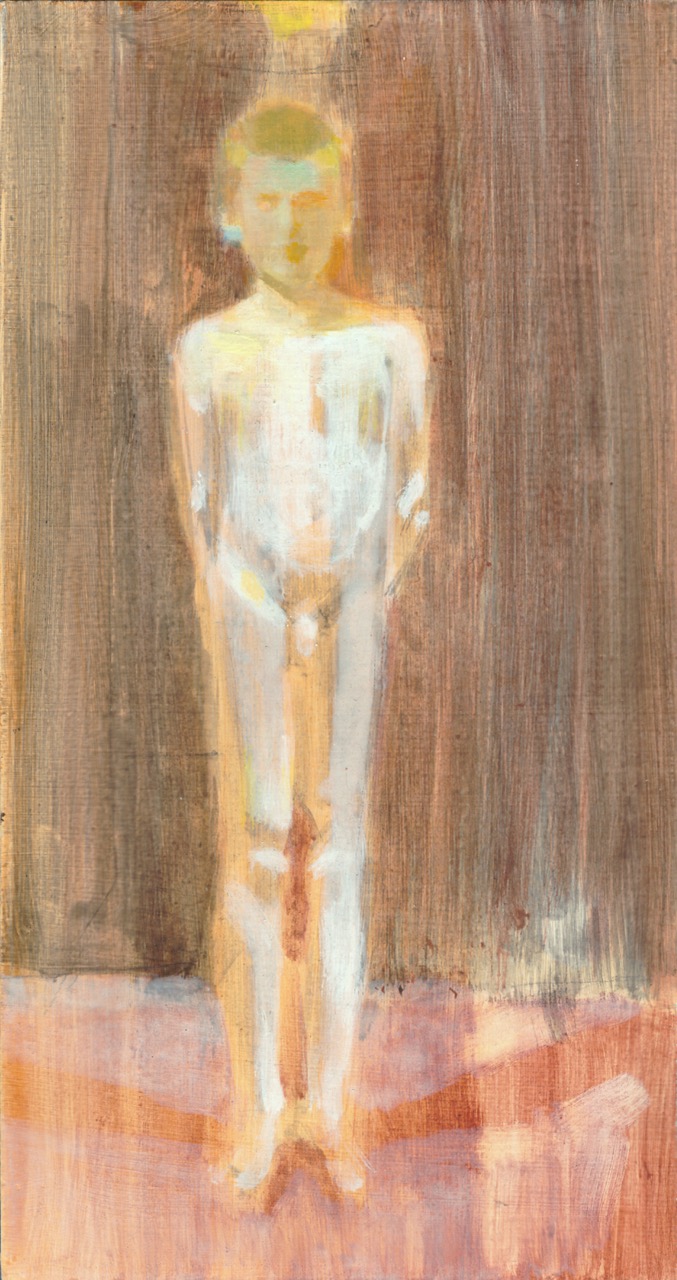

Kerstin Pfefferkorn’s paintings span a wide range – both in the manner of painting as well as in the level of the depicted. One’s own motifs become closer to the foreign, anonymous motifs, and conversely, the motifs of the unknown gain a familiarity that is akin to kinship. The painting style itself suggests a traditional temperament, a classical illusion of spatial depth, but persists in an abstract imprimitura that curbs illusionistic ex- pectations and sharpens the imagination. Overall, Kerstin Pfefferkorn’s painting testifies to the depiction of a mysterious intimacy, a discreet fusion of the objective and emotional worlds.

Man is the preferred subject of her paintings. In the depictions, the human being is completely depicted, and yet something is missing and something else is added. The human being is more than the sum of his organs. A human being recognises his counterpart and is recognised by his counterpart. Do we recognise each other by the number of our fin- gers? Is one recognised by the curvature of the auricle? Is it impossible to recognise oneself if the auricle is curved in the same way as another person’s? Or if you count the same number of fingers? Probably not. So what is the more in the sum? What is the specific knowing or being?

Without a doubt, recognition has something to do with knowledge, i.e. one recognises something again, one recognises what one remembers. To recognise is to see what was. But nothing is as unreliable as what we remember. Our mind almost constantly invents memories to fill the gaps in our understanding of the world as a whole, resulting in an illusion, but one that lulls us into a sense of security. This reassurance contrasts with painting, which is basically the most implausible form of illusion–making, with a history of applying every imaginable realistic illusion formation despite the fundamental two–dimensionality of this medium. Not to hold anything to be true that is not so clearly recognised that it cannot be doubted. Doubt about summation runs like a ghost through Renaissance, Baroque and Realist painting, finally manifesting itself in 20th century painting. Contrary to the summation of exactitudes, Cézanne follows the trail of the eye and recognises that the realistic representation does not lie in the sum of the individual material parts of a landscape, but in the emotional content with which the fragments are charged. Like Giacometti, who in his sculptures and paintings discovers the un- bridgeability of the distance to the other person and is able to overcome perceived light years between people by looking into the eyes of the other, to which everything else is subordinated to the point of insignificance.

The search for meaning is thus not on the outside, but on the inside of the observer. The emotional attachment to the subject becomes the dominant theme of the century.

Kerstin Pfefferkorn paints people who are blurred in appearance, contourless, and in their blurriness can hardly be separated from the inde- terminate background. They are complete, i.e. no sketches, no fragments, but for their part they renounce the impression of the completeness of the sum. By the use of soft, blurred lines and delicate hues, the contours of the figures are blurred and their features only vaguely indicated. Between visibility and invisibility, between presence and absence, the figures seem to remain in a kind of intermediate state. Included in this blurring are also the concrete features of a particular person, regardless of whether he or she is known or unknown. There may be a completely unknown person in the picture. But so much remains hinted at and at the same time left vague that one intuitively believes to recognise the posture and feels reminded of someone familiar.

Peripetia.

Standing by a river. The view upstream. The view downstream. On this bank. Opposite the other bank. On the other side, shot–up villages. Dead horses. Corpses. A white arm reaching out of the water for a dead child. The pressure from the east. At the back, the solidarity of money. At the core of the fortress. At the bottom of the fortress well. Dried up. Downthere, the homeland is a space made of time, similar to the city across the river, an intermediate realm in which people become more and more transparent until one day they are forgotten; disappeared. At the bottom of this well, man is a fragile vessel, more fragile than the lifeless bodies of history in the shattered villages. But even here in the homely twilight sleep, the notorious doubt hums, what is unmistakable in the world, that it remains a mistake that the dead are dead.

Extinction and return.

The great thoughts of the 20th century worked to liquidate their autonomy, to dispossess the thinker and make him disappear. The last- ing is the fleeting. The ephemeral remains. That was the canon of the avant–garde. And the avant–garde, one reads, has been overtaken by postmodernism. A state of time that has lost the future. In mid–November 2022, eight billion people populate the earth. Never before have so many people lived on earth at the same time. By that time, about 110 billion people are supposed to have lived on earth. So the eight billion people living on earth today make up about eight percent of that number. When Jesus lived, there were about 140 million people living on the whole earth. With the number of living people, everything has become bigger and more monstrous. The wars bloodier. The exterminations more massive. The exploitation more boundless. The language more helpless. The ideas more imprecise. The idea of equality negates every individual. It elevates the apocalypse to the guiding global fantasy of the twentieth century, and consumption promises the resolution of this erasure through individuality. Modern religion consists in the expulsion of the self into redemption as an individual. What remains is eternal resurrection.

Beneath this shell slumbers an experience of the eternal self, a basis of communication. The receiver can only understand what he already knows. From the “liquidation” of the autonomy of individual sensitivities follows the attribution of the generally possible, the maximum experien- tial space of the individual, who differs from others only in his narrative. If one can transfer precisely this narrative in the blur, present but not determining, it becomes clear what is possible, what being is.

In Goethe, Prometheus sneers with the empowerment of man against the gods, against servitude, for the revolutionary moment:

“Did you think /I should hate life, /Flee in deserts, /Because not all boys’ mornings/ Ripened dreams of blossoms?”

A scar remained from Heracles’ liberation. Prometheus could easily have freed himself had he not feared the eagle, weaponless and exhausted from millennia of torture.

What do boys dream of? Empowerment? Magic? Activity? Owning the world? Displacing the father? Challenging the tyranny of the father’s possession of the mother? Well, Prometheus was indeed involved in dis- placing the deity of the Titans, to which he belonged, and supporting Zeus as the new ruler. Rebel and revolt once again? Yet an Oedipal fantasy of annihilation. Prometheus himself suggests that there will be no mourning when the Oedipal conflict is overcome, the role of Zeus is accepted and humans emancipate themselves in the next step. Like those who did not know that hell was invented on earth, unsus- pecting, friendly, gentle they sit there, the boys, children, girls, lovingly painted by Kerstin Pfefferkorn, quietly in the picture in front of the fence or as a portrait up to the chest or standing on a meadow, waiting, intimate and animated by the timelessness of every action. The gaze into the gar- den is determined by the same eternity as the gaze into the distance. The father is absent. The mother as a young woman, inwardly calm. As if the life through which all must pass could be preserved by a single example, the image of a boy Enoch is mentioned, who so meekly and obediently walked the path of peace that he was lifted up by God without having to die. This gate without death is reserved for the experiential space of the infant at Enoch’s side, who in his limitedness has a special view of his surroundings. A Frenchman refers to this childhood experience: “The house of childhood is always comforting in memory, no matter how small, narrow or cold it actually was; the house is man’s first impression of the world, in the house his life begins, and in the memory of the house it remains a timeless shelter like a shell. Precisely because the house of childhood is given dream values in memory, memory merges with imagination. Another says that this is why “we are never really historians, but always only little poets” when we remember our childhood. We do not simply reproduce the house of childhood in memory, but interpret the feeling of childhood security into a felt memory image of the house.

Immortal all. And immortal all. Do not fear /Death at seventeen, /At seventy. There is only /being and light, /neither darkness nor death on this earth. /We have stood at the edge of the sea for a long time, /I am with those who take the nets, /When immortality moves like a swarm. /... /I call any century, /I build a house in it and go inside.

Cheers for the people.

I call any century, /I build a house in it and go in. Enoch found his house, his century, his home with God. Home is a space made of time. And instead of dissolving into nothingness, the boys in Kerstin Pfefferkorn’s pictures seem to find themselves in the transparent fluid between the centuries, searching for themselves over unheard–of periods of time with gazes in order to be able to manifest themselves in the eyes of others, searching for any century ... in order to then accept the order of Prometheus, who had worked his way back on the shoulder of his liberator and assumed the posture of the victor there, riding on a sweaty horse towards the cheers of the people.

Kerstin Pfefferkorn’s paintings span a wide range – both in the manner of painting as well as in the level of the depicted. One’s own motifs become closer to the foreign, anonymous motifs, and conversely, the motifs of the unknown gain a familiarity that is akin to kinship. The painting style itself suggests a traditional temperament, a classical illusion of spatial depth, but persists in an abstract imprimitura that curbs illusionistic ex- pectations and sharpens the imagination. Overall, Kerstin Pfefferkorn’s painting testifies to the depiction of a mysterious intimacy, a discreet fusion of the objective and emotional worlds.

Man is the preferred subject of her paintings. In the depictions, the human being is completely depicted, and yet something is missing and something else is added. The human being is more than the sum of his organs. A human being recognises his counterpart and is recognised by his counterpart. Do we recognise each other by the number of our fin- gers? Is one recognised by the curvature of the auricle? Is it impossible to recognise oneself if the auricle is curved in the same way as another person’s? Or if you count the same number of fingers? Probably not. So what is the more in the sum? What is the specific knowing or being?

Without a doubt, recognition has something to do with knowledge, i.e. one recognises something again, one recognises what one remembers. To recognise is to see what was. But nothing is as unreliable as what we remember. Our mind almost constantly invents memories to fill the gaps in our understanding of the world as a whole, resulting in an illusion, but one that lulls us into a sense of security. This reassurance contrasts with painting, which is basically the most implausible form of illusion–making, with a history of applying every imaginable realistic illusion formation despite the fundamental two–dimensionality of this medium. Not to hold anything to be true that is not so clearly recognised that it cannot be doubted. Doubt about summation runs like a ghost through Renaissance, Baroque and Realist painting, finally manifesting itself in 20th century painting. Contrary to the summation of exactitudes, Cézanne follows the trail of the eye and recognises that the realistic representation does not lie in the sum of the individual material parts of a landscape, but in the emotional content with which the fragments are charged. Like Giacometti, who in his sculptures and paintings discovers the un- bridgeability of the distance to the other person and is able to overcome perceived light years between people by looking into the eyes of the other, to which everything else is subordinated to the point of insignificance.

The search for meaning is thus not on the outside, but on the inside of the observer. The emotional attachment to the subject becomes the dominant theme of the century.

Kerstin Pfefferkorn paints people who are blurred in appearance, contourless, and in their blurriness can hardly be separated from the inde- terminate background. They are complete, i.e. no sketches, no fragments, but for their part they renounce the impression of the completeness of the sum. By the use of soft, blurred lines and delicate hues, the contours of the figures are blurred and their features only vaguely indicated. Between visibility and invisibility, between presence and absence, the figures seem to remain in a kind of intermediate state. Included in this blurring are also the concrete features of a particular person, regardless of whether he or she is known or unknown. There may be a completely unknown person in the picture. But so much remains hinted at and at the same time left vague that one intuitively believes to recognise the posture and feels reminded of someone familiar.

Peripetia.

Standing by a river. The view upstream. The view downstream. On this bank. Opposite the other bank. On the other side, shot–up villages. Dead horses. Corpses. A white arm reaching out of the water for a dead child. The pressure from the east. At the back, the solidarity of money. At the core of the fortress. At the bottom of the fortress well. Dried up. Downthere, the homeland is a space made of time, similar to the city across the river, an intermediate realm in which people become more and more transparent until one day they are forgotten; disappeared. At the bottom of this well, man is a fragile vessel, more fragile than the lifeless bodies of history in the shattered villages. But even here in the homely twilight sleep, the notorious doubt hums, what is unmistakable in the world, that it remains a mistake that the dead are dead.

Extinction and return.

The great thoughts of the 20th century worked to liquidate their autonomy, to dispossess the thinker and make him disappear. The last- ing is the fleeting. The ephemeral remains. That was the canon of the avant–garde. And the avant–garde, one reads, has been overtaken by postmodernism. A state of time that has lost the future. In mid–November 2022, eight billion people populate the earth. Never before have so many people lived on earth at the same time. By that time, about 110 billion people are supposed to have lived on earth. So the eight billion people living on earth today make up about eight percent of that number. When Jesus lived, there were about 140 million people living on the whole earth. With the number of living people, everything has become bigger and more monstrous. The wars bloodier. The exterminations more massive. The exploitation more boundless. The language more helpless. The ideas more imprecise. The idea of equality negates every individual. It elevates the apocalypse to the guiding global fantasy of the twentieth century, and consumption promises the resolution of this erasure through individuality. Modern religion consists in the expulsion of the self into redemption as an individual. What remains is eternal resurrection.

Beneath this shell slumbers an experience of the eternal self, a basis of communication. The receiver can only understand what he already knows. From the “liquidation” of the autonomy of individual sensitivities follows the attribution of the generally possible, the maximum experien- tial space of the individual, who differs from others only in his narrative. If one can transfer precisely this narrative in the blur, present but not determining, it becomes clear what is possible, what being is.

In Goethe, Prometheus sneers with the empowerment of man against the gods, against servitude, for the revolutionary moment:

“Did you think /I should hate life, /Flee in deserts, /Because not all boys’ mornings/ Ripened dreams of blossoms?”

A scar remained from Heracles’ liberation. Prometheus could easily have freed himself had he not feared the eagle, weaponless and exhausted from millennia of torture.

What do boys dream of? Empowerment? Magic? Activity? Owning the world? Displacing the father? Challenging the tyranny of the father’s possession of the mother? Well, Prometheus was indeed involved in dis- placing the deity of the Titans, to which he belonged, and supporting Zeus as the new ruler. Rebel and revolt once again? Yet an Oedipal fantasy of annihilation. Prometheus himself suggests that there will be no mourning when the Oedipal conflict is overcome, the role of Zeus is accepted and humans emancipate themselves in the next step. Like those who did not know that hell was invented on earth, unsus- pecting, friendly, gentle they sit there, the boys, children, girls, lovingly painted by Kerstin Pfefferkorn, quietly in the picture in front of the fence or as a portrait up to the chest or standing on a meadow, waiting, intimate and animated by the timelessness of every action. The gaze into the gar- den is determined by the same eternity as the gaze into the distance. The father is absent. The mother as a young woman, inwardly calm. As if the life through which all must pass could be preserved by a single example, the image of a boy Enoch is mentioned, who so meekly and obediently walked the path of peace that he was lifted up by God without having to die. This gate without death is reserved for the experiential space of the infant at Enoch’s side, who in his limitedness has a special view of his surroundings. A Frenchman refers to this childhood experience: “The house of childhood is always comforting in memory, no matter how small, narrow or cold it actually was; the house is man’s first impression of the world, in the house his life begins, and in the memory of the house it remains a timeless shelter like a shell. Precisely because the house of childhood is given dream values in memory, memory merges with imagination. Another says that this is why “we are never really historians, but always only little poets” when we remember our childhood. We do not simply reproduce the house of childhood in memory, but interpret the feeling of childhood security into a felt memory image of the house.

Immortal all. And immortal all. Do not fear /Death at seventeen, /At seventy. There is only /being and light, /neither darkness nor death on this earth. /We have stood at the edge of the sea for a long time, /I am with those who take the nets, /When immortality moves like a swarm. /... /I call any century, /I build a house in it and go inside.

Cheers for the people.

I call any century, /I build a house in it and go in. Enoch found his house, his century, his home with God. Home is a space made of time. And instead of dissolving into nothingness, the boys in Kerstin Pfefferkorn’s pictures seem to find themselves in the transparent fluid between the centuries, searching for themselves over unheard–of periods of time with gazes in order to be able to manifest themselves in the eyes of others, searching for any century ... in order to then accept the order of Prometheus, who had worked his way back on the shoulder of his liberator and assumed the posture of the victor there, riding on a sweaty horse towards the cheers of the people.

Installation Views

×

![]()

Works

-

Kerstin PfefferkornBildnis vor Zaun, 2018

Kerstin PfefferkornBildnis vor Zaun, 2018 -

Kerstin PfefferkornDoppelakt, 2018

Kerstin PfefferkornDoppelakt, 2018 -

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenakt auf Goldocker,

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenakt auf Goldocker, -

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenakt schmal, 2021

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenakt schmal, 2021 -

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenporträt auf Goldocker, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenporträt auf Goldocker, 2022 -

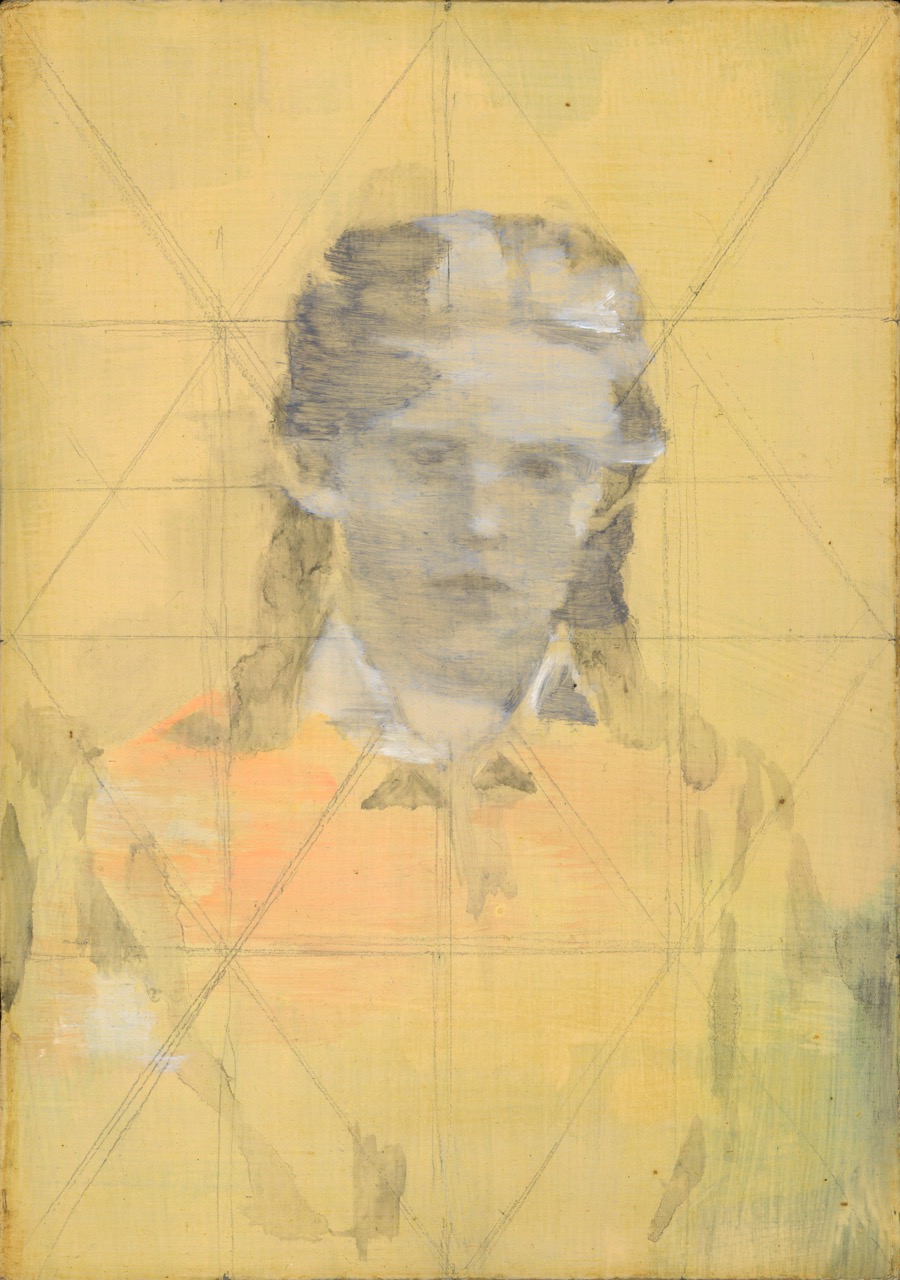

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenporträt Grisaille, 2023

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenporträt Grisaille, 2023 -

Kerstin PfefferkornKind auf Wiese, 2016

Kerstin PfefferkornKind auf Wiese, 2016 -

Kerstin PfefferkornMädchen mit Zöpfen, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornMädchen mit Zöpfen, 2022 -

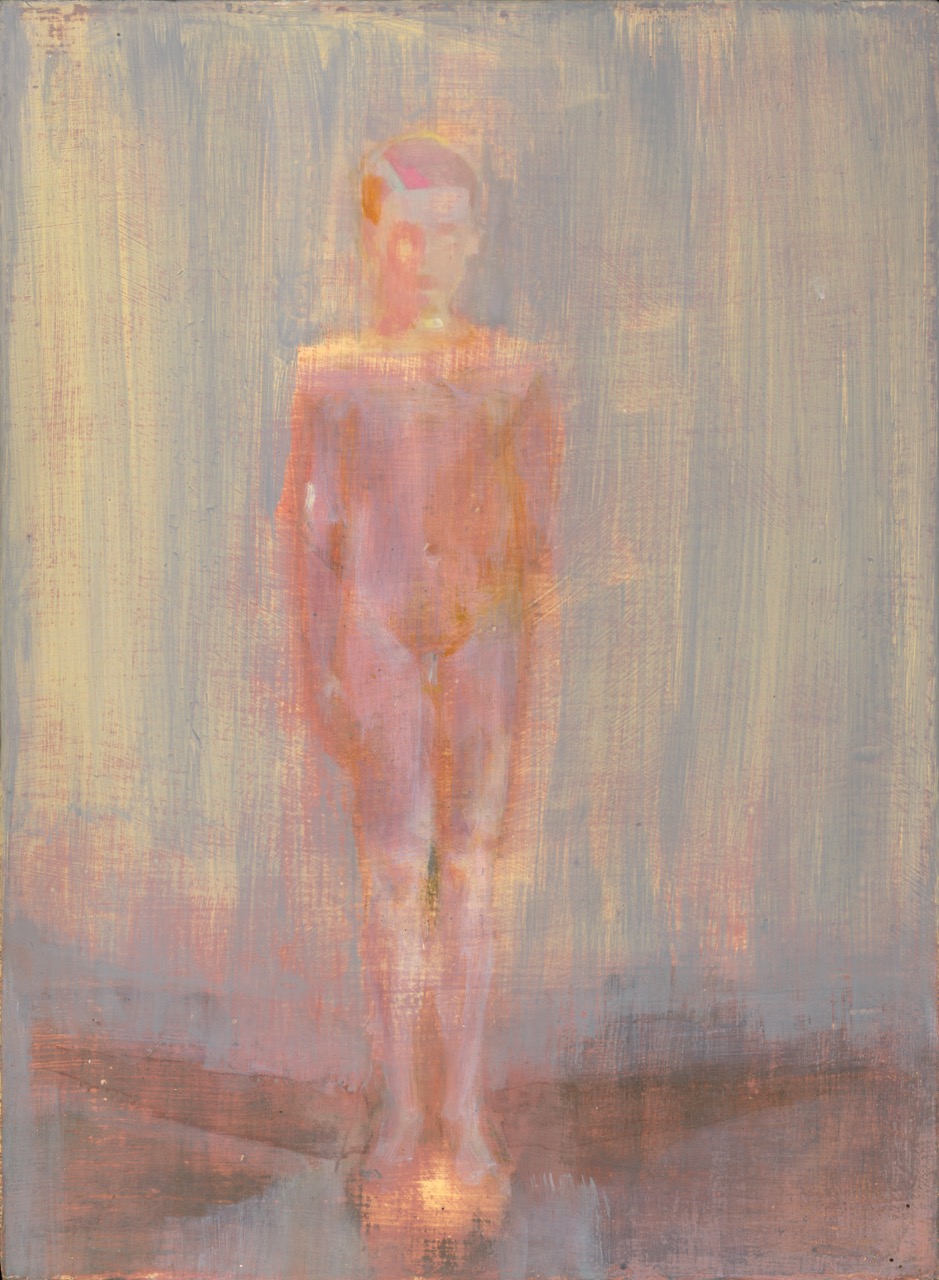

Kerstin PfefferkornMädchenackt frontal auf Goldocker, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornMädchenackt frontal auf Goldocker, 2022 -

Kerstin PfefferkornMädchenporträt auf Goldocker, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornMädchenporträt auf Goldocker, 2022 -

Kerstin PfefferkornFrau mit Buch, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornFrau mit Buch, 2022 -

Kerstin PfefferkornPorträt Junger Mann auf Goldocker, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornPorträt Junger Mann auf Goldocker, 2022 -

Kerstin PfefferkornSchaukel, 2017

Kerstin PfefferkornSchaukel, 2017 -

Kerstin PfefferkornFrau mit Halstuch, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornFrau mit Halstuch, 2022 -

Kerstin PfefferkornHalbbildnis auf Rot, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornHalbbildnis auf Rot, 2022 -

Kerstin PfefferkornHenoch, 2021-23

Kerstin PfefferkornHenoch, 2021-23 -

Kerstin PfefferkornJungen mit Locken Grisaille, 2023

Kerstin PfefferkornJungen mit Locken Grisaille, 2023 -

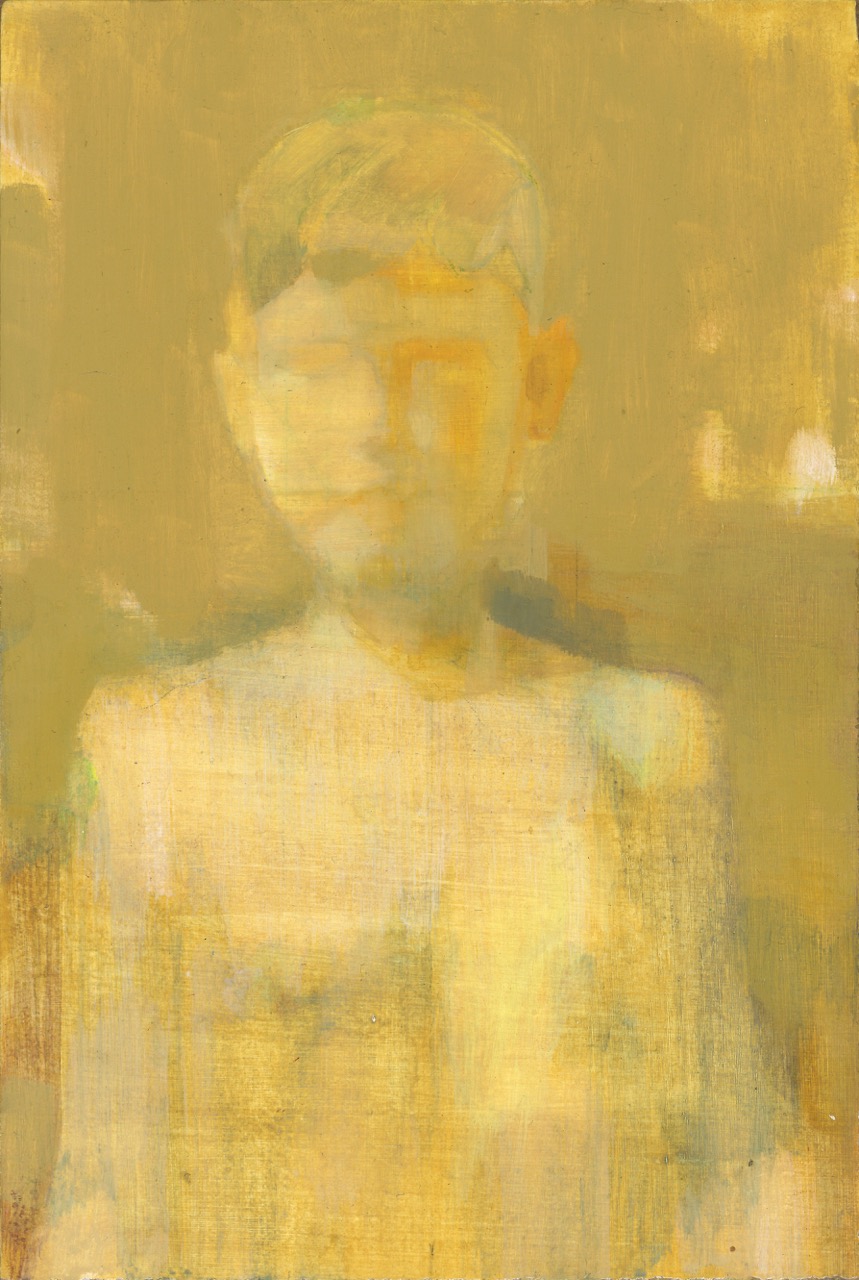

Kerstin PfefferkornHalbakt auf Goldocker, 2023

Kerstin PfefferkornHalbakt auf Goldocker, 2023 -

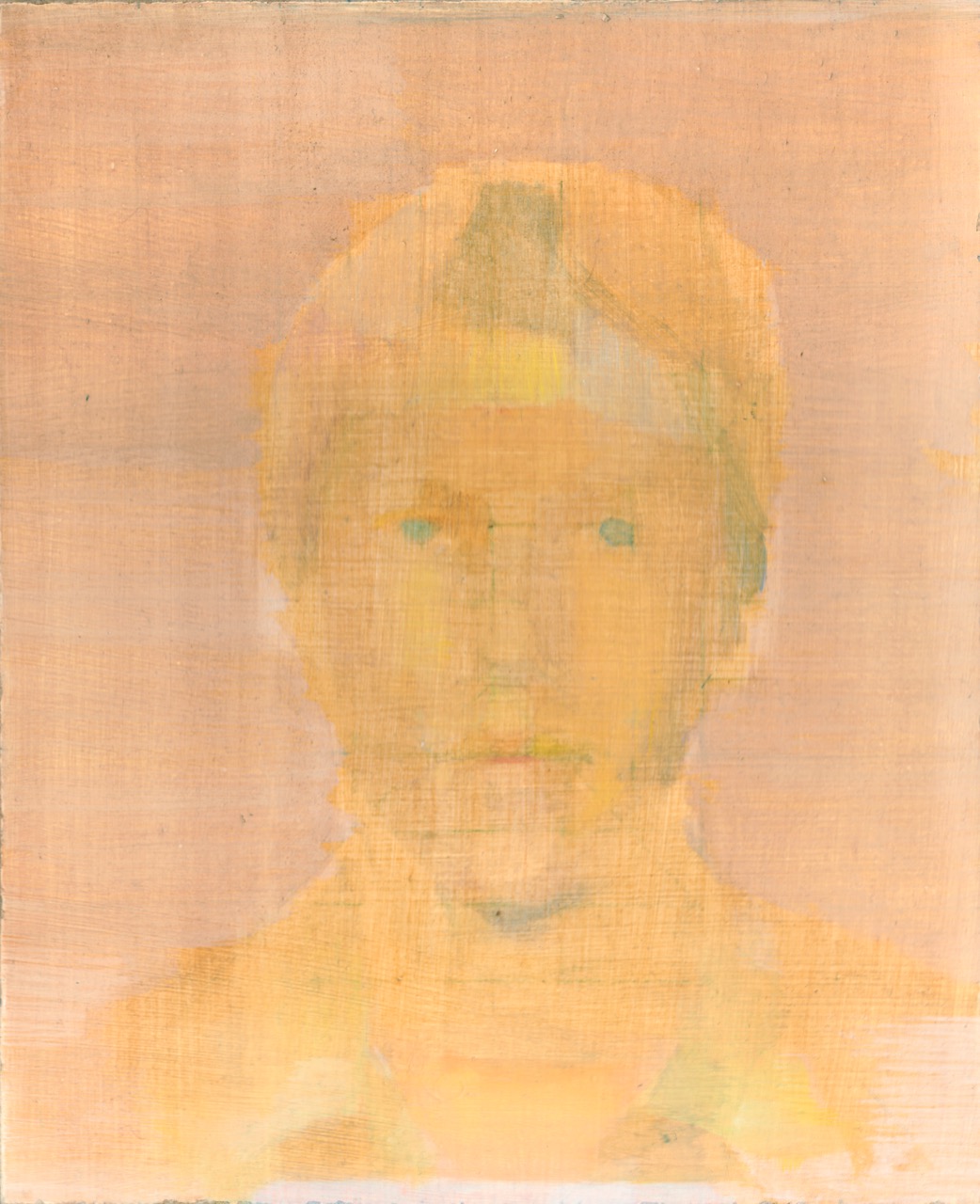

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenporträt Grisaille mit Rosa, 2021

Kerstin PfefferkornJungenporträt Grisaille mit Rosa, 2021 -

Kerstin PfefferkornJunge Frau sitzend mit Kleid, 2023

Kerstin PfefferkornJunge Frau sitzend mit Kleid, 2023 -

Kerstin PfefferkornHalbbildnis auf Grün, 2019

Kerstin PfefferkornHalbbildnis auf Grün, 2019 -

Kerstin PfefferkornGartenblick, 2011

Kerstin PfefferkornGartenblick, 2011 -

Kerstin PfefferkornSitzender vor Blattwerk, 2018-23

Kerstin PfefferkornSitzender vor Blattwerk, 2018-23 -

Kerstin PfefferkornPflanze auf Rosa, 2018-23

Kerstin PfefferkornPflanze auf Rosa, 2018-23 -

Kerstin PfefferkornWaldrand, 2011

Kerstin PfefferkornWaldrand, 2011 -

Kerstin PfefferkornMädchen im Kleid, 2023

Kerstin PfefferkornMädchen im Kleid, 2023 -

Kerstin PfefferkornSitzender im Dunkel, 2022

Kerstin PfefferkornSitzender im Dunkel, 2022 -

Kerstin PfefferkornStehender mit Strauss, 2019

Kerstin PfefferkornStehender mit Strauss, 2019

×